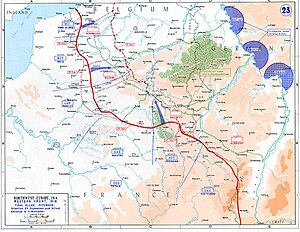

The Hundred Days Offensive was the final period of the First World War, during which the Allies launched a series of offensives against the Central Powers on the Western Front from 8 August-11 November 1918, beginning with the Battle of Amiens. The offensive forced the German armies to retreat beyond the Hindenburg Line and was followed by an armistice. The Hundred Days Offensive does not refer to a specific battle or unified strategy, but rather the rapid sequences of Allied victories starting with the Battle of Amiens.

The Hundred Days Offensive was the final period of the First World War, during which the Allies launched a series of offensives against the Central Powers on the Western Front from 8 August-11 November 1918, beginning with the Battle of Amiens. The offensive forced the German armies to retreat beyond the Hindenburg Line and was followed by an armistice. The Hundred Days Offensive does not refer to a specific battle or unified strategy, but rather the rapid sequences of Allied victories starting with the Battle of Amiens.

the great German Spring Offensives on the Western Front in 1918, beginning with Operation Michael had petered out by July. The Germans had advanced to the Marne River but failed to achieve a decisive breakthrough

. When Operation Marne-Rheimsended in July, the Allied supreme commander, the French Ferdinand Foch, ordered a counter-offensive which became theSecond Battle of the Marne. The Germans, recognising their untenable position, withdrew from the Marne towards the north, for which victory Foch was promoted Marshal of France

. When Operation Marne-Rheimsended in July, the Allied supreme commander, the French Ferdinand Foch, ordered a counter-offensive which became theSecond Battle of the Marne. The Germans, recognising their untenable position, withdrew from the Marne towards the north, for which victory Foch was promoted Marshal of France

Foch considered the time had arrived for the Allies to return to the offensive. The Americans were now present in France in large numbers, and their presence invigorated the Allied armies.

The United States was unprepared for its entrance into the First World War. In April 1917, the American Army numbered only 300,000 including all the National Guard units that could be federalized for national service.

The Army's arsenal of war supplies was non-existent and its incursion into Mexico the previous year pointed out the severe deficiencies in its military structure including training, organization, and supply.

Their commander, General John J. Pershing, was keen to use his army in an independent role.When the European continent had erupted in conflict in 1914, President Wilson declared America's neutrality. He proposed an even-handed approach towards all the belligerents that was to be maintained in both "thought

and deed." The President steadfastly maintained his hope of a peaceful solution to the conflict despite the protestations of those (including former president Roosevelt) convinced that events in Europe would inevitably draw America into the war. In 1916, Wilson campaigned for reelection on a peace platform with the slogan "He kept us out of war."

Events in Europe altered Wilson's outlook. Germany's campaign of unrestricted submarine warfare, the loss of American lives on the high seas, the sinking of the Lusitania and other ships and the prospect that Germany would not change her policies compelled a reluctant Wilson to ask Congress for a declaration of war in April 1917. Things were not going well for the Allies at the time. Russia erupted in revolution in March 1917 and would soon be out of the war altogether. Italy suffered a major defeat when the Austrians captured over 275,000 soldiers in the Battle of Caporetto forcing the British and French to divert troops from the Western Front to keep Italy in the war.

The situation remained stagnate on the Western Front - and worse. Mutiny spread throughout the French Army raising the fear that her armed forces may collapse from within. In Britain, the German submarine campaign was so successful that predictions foresaw Britain's collapse within a matter of months.

The Allies looked to America for salvation with the expectation that the industrial strength of the United States would replenish the supply of war material necessary for victory.

In most cases these expectations were unrealistic. For example, the US built no more than 800 airplanes prior to 1917, and yet the French premier called on the US to immediately produce 2,000 airplanes per month

Additionally, the Allies expected the United States to provide an unlimited supply of manpower they could absorb into their beleaguered divisions. |

Wilson selected General John J. Pershing (called "Black Jack" after he commanded the famous 10th cavalry in he 1890s) to head the American Expeditionary Force. Pershing left for Europe with a mandate from Wilson to cooperate with Allied forces under the following proviso - "that the forces of the United States are a separate and distinct component of the combined forces the identity of which must be preserved."

In other words, there would be no wholesale melding of American soldiers into the British and French armies as the Allied commanders hoped. The United States would fight under its own flag and its own leadership. This proved to be a bone of contention among the Allies for the rest of the war.

America's buildup was slow - Pershing called for a million men, Congress replied it could muster 420,000 by spring 1918. The anticipated cornucopia of military supplies from America never materilaized.

For the most part the doughboys fought with equipment supplied by the Allies (including the distinctive helmet provided by the British). American troops saw their first action in May 1918 in fighting alone the Marne River. In September,

Pershing ordered an all-out attack in the Saint-Mihiel area of Eastern France. Casualties were high but the attack forced a German retreat that (combined with other Allied offensives along the Western Front) put the entire German army on the run.

Pershing ordered an all-out attack in the Saint-Mihiel area of Eastern France. Casualties were high but the attack forced a German retreat that (combined with other Allied offensives along the Western Front) put the entire German army on the run.

In early October, the Americans pushed through the Argonne Forest. The German High Command began to crack in the face of the persistent Allied onslaught. General Ludendorff was forced to resign and flee to Sweden, mutiny reared its ugly head among the Kaiser's naval units, and the Kaiser himself abdicated on November 9. On November 11, Germany signed an armistice ending the war.

Pershing had thrown almost 1.2 million Americans into the battle. Casualties numbered 117,000. With the war over, Americans wished to forget Europe's troubles and return to "the good old days." Congress rejected Wilson's call for participation in the League of Nations. The nation turned inward again. America had been the provider of many war parts for the French and British armies while it was neutral. Ironically, now in war, both the British and French armies provided the first arriving American troops with equipment and uniforms. The AEF was given French artillery guns (the 75

and 155mm) while the British provided mortars, machine guns, steel helmets and some uniforms.

and 155mm) while the British provided mortars, machine guns, steel helmets and some uniforms.The lack of speed with which the AEF was sent to Europe was later criticised by David Lloyd George. The 1st Division AEF landed in France in June 1917. The 2nd Division did not arrive until September and by October 31st, 1917, the AEF only numbered 6,064 officers and 80,969 men. In roughly the same time span in 1914, the BEF had got 354,750 men into the field. Nine months after America declared war, there were 175,000 American troops in Western Europe. In the same time span of nine months from 1914 to

The 1st Division AEF landed in France in June 1917. The 2nd Division did not arrive until September and by October 31st, 1917, the AEF only numbered 6,064 officers and 80,969 men. In roughly the same time span in 1914, the BEF had got 354,750 men into the field. Nine months after America declared war, there were 175,000 American troops in Western Europe. In the same time span of nine months from 1914 to  1915, Britain had put 659,104 men into the various theatres of war. Therefore, in 1917, despite her strength on paper, America played little part in the war activities of that year.

1915, Britain had put 659,104 men into the various theatres of war. Therefore, in 1917, despite her strength on paper, America played little part in the war activities of that year.

The 1st Division AEF landed in France in June 1917. The 2nd Division did not arrive until September and by October 31st, 1917, the AEF only numbered 6,064 officers and 80,969 men. In roughly the same time span in 1914, the BEF had got 354,750 men into the field. Nine months after America declared war, there were 175,000 American troops in Western Europe. In the same time span of nine months from 1914 to

The 1st Division AEF landed in France in June 1917. The 2nd Division did not arrive until September and by October 31st, 1917, the AEF only numbered 6,064 officers and 80,969 men. In roughly the same time span in 1914, the BEF had got 354,750 men into the field. Nine months after America declared war, there were 175,000 American troops in Western Europe. In the same time span of nine months from 1914 to  1915, Britain had put 659,104 men into the various theatres of war. Therefore, in 1917, despite her strength on paper, America played little part in the war activities of that year.

1915, Britain had put 659,104 men into the various theatres of war. Therefore, in 1917, despite her strength on paper, America played little part in the war activities of that year.However, was America to blame for the lack of speed in her military build-up? Whereas Britain had spent time in 1914 planning for war and creating 6 divisions for the European campaign, America was all but starting from the beginning. In peacetime, the American army only numbered 190,000 and they were spread across America. Now with the declaration of war, these men had to move to the eastern seaboard where many camps had to be built to accommodate them before they sailed across the Atlantic. French ports had to be greatly expanded to handle the influx of men and the French rail network in the region had to be expanded.

Pershing also wanted the AEF to be perfectly ready for combat. He did not want what Haig and Pétain wanted - that American forces should be used to fill in where the Allies were weak. Pershing wanted an independent fighting unit that was well-trained and self-contained. Therefore, when the Germans launched their great offensive of March 1918, there was only one American division in the Allied lines - with three divisions in training areas. The series of German offensives from March to July 1918 posed great dangers to the French and British armies. Paris was threatened and on two occasions, the British were nearly driven into the Channel on two occasions. But in all of these attacks, the Americans played little part.

However, the German spring offensive had made Pershing realise that he needed to change his course of action. In June it was agreed that American troops would be sent to France from America without space-occupying equipment that could be provided by the French and British once the Americans were in France. In June and July 1918, America sent over 584,000 men. The American merchant marine could not cope with such numbers - so the British merchant marine was used as well. The German army could not hope to match such numbers that arrived in a very short space of time.

On July 18th, 1918, the French launched a major attack against the Germans from the Forest of Villers-Cotterêts.  This attack included two American divisions - a total of 54,000 men. By August 1918, there were nearly 1,500,000 American troops in France. Germany could only muster 300,000 youths. The Allies were planning for a major attack in 1919 that would be led by 100 American divisions. Faced with such odds, the Germans had no choice but to look for a way out of fighting. This led to the armistice in November 1918 that itself led to the Treaty of Versailles in June 1919.

This attack included two American divisions - a total of 54,000 men. By August 1918, there were nearly 1,500,000 American troops in France. Germany could only muster 300,000 youths. The Allies were planning for a major attack in 1919 that would be led by 100 American divisions. Faced with such odds, the Germans had no choice but to look for a way out of fighting. This led to the armistice in November 1918 that itself led to the Treaty of Versailles in June 1919.

This attack included two American divisions - a total of 54,000 men. By August 1918, there were nearly 1,500,000 American troops in France. Germany could only muster 300,000 youths. The Allies were planning for a major attack in 1919 that would be led by 100 American divisions. Faced with such odds, the Germans had no choice but to look for a way out of fighting. This led to the armistice in November 1918 that itself led to the Treaty of Versailles in June 1919.

This attack included two American divisions - a total of 54,000 men. By August 1918, there were nearly 1,500,000 American troops in France. Germany could only muster 300,000 youths. The Allies were planning for a major attack in 1919 that would be led by 100 American divisions. Faced with such odds, the Germans had no choice but to look for a way out of fighting. This led to the armistice in November 1918 that itself led to the Treaty of Versailles in June 1919.A number of proposals were considered, and finally Foch agreed on a proposal by Field Marshal Douglas Haig, the commander of the British Expeditionary Force (BEF), to strike on the Somme, east of Amiens and southwest of the 1916 battlefield of theBattle of the Somme, with the intention of forcing the Germans away from the vital

Amiens-Paris railway.

Amiens-Paris railway.The Somme was chosen as a suitable site for the offensive for several reasons. As in 1916, it marked the boundary between the BEF and the French armies, in this case defined by the Amiens-Roye road, allowing the two armies to cooperate

. Also the Picardycountryside provided a good surface for tanks, which was not the case in Flanders. Finally, the German defences, manned by the German Second Army of General Georg von der Marwitz

, were relatively weak, having been subjected to continual raiding by the Australians in a process termed Peaceful Penetration.

, were relatively weak, having been subjected to continual raiding by the Australians in a process termed Peaceful Penetration.