Friday, 23 November 2012

Tuesday, 20 November 2012

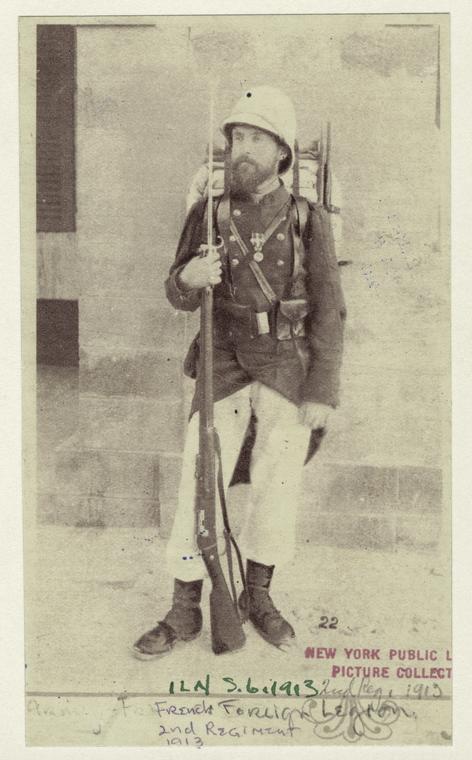

the legion , the early years

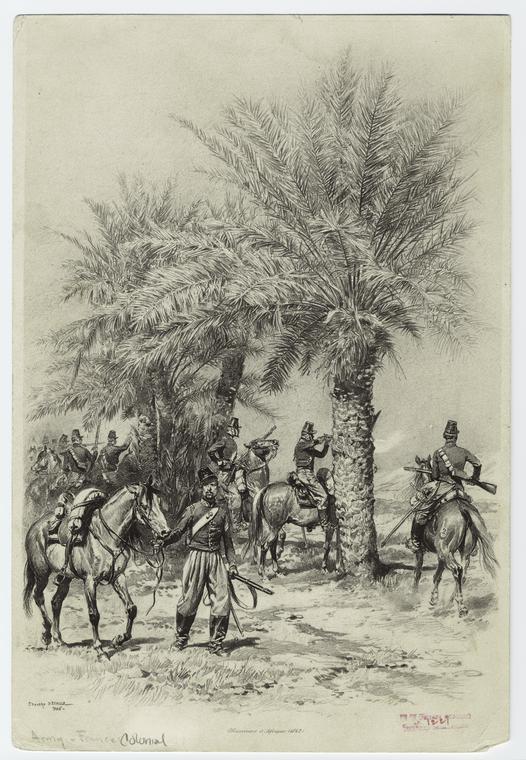

![View Smaller Image [French soldiers, 19th century.]](http://images.nypl.org/index.php?id=830537&t=w) France's experience in Africa was conditioned by two things. First, France had a longstanding interest in the region bordering the Mediterranean Sea thanks to its own coast line between Italy and Spain, its active role in the

France's experience in Africa was conditioned by two things. First, France had a longstanding interest in the region bordering the Mediterranean Sea thanks to its own coast line between Italy and Spain, its active role in the The French first occupied African soil in Algeria in 1830 while trying to reestablish their authority in the Mediterranean.

Since 1684, when Louis XIV ordered the bombardment of Algiers in an effort to retrieve Christian slaves, to the reprisals launched after the Napoleonic Wars against cities along the "Barbary Coast" that supported pirates,

Since 1684, when Louis XIV ordered the bombardment of Algiers in an effort to retrieve Christian slaves, to the reprisals launched after the Napoleonic Wars against cities along the "Barbary Coast" that supported pirates, the French viewed North Africa as a source of opposition. After peace was restored in 1815, the piracy stopped but relations remained very tense.

the French viewed North Africa as a source of opposition. After peace was restored in 1815, the piracy stopped but relations remained very tense.

In 1828 Hussein, the Dey of Algiers, struck French consul Pierre Deval with his fly whisk. Deval reported it back to his king as an insult and two years later, Charles X used it as a pretext to invade Algiers. The invasion began on 5 July 1830 and the French quickly occupied the city. That ignited resistance in the Algerian interior and during two wars that were fought between 1832 and 1837, rural Berbers united behind Abd al-Qadir (alternate spelling: Abd el-Kader) to oppose the French.

After a third war against al-Qadir's forces failed to defeat him in 1840-1841, the French began to use terror tactics that included the destruction of wells and crops. On two occasions, French military forces pursued al-Qadir into land claimed by Morocco--an independent country--and finally captured him in 1847.

To quiet Moroccan protests, France signed the Treaty of Tangier on September 10, 1844 which provided French recognition of Moroccan independence and promises not to invade Morocco again.

Berber uprisings continued in central Algeria until 1873 when the French occupied the strategically-located oasis of El Golea, 540 miles south of Algiers. Resistance continued deeper in the desert and in 1880-1881, the nomadic Tuaregs wiped out an expedition led by the French Colonel Paul Flatters as it tried to survey a railroad route acress the Sahara Desert. Resistance continued in the desert until 1932 when the use of airplanes, radios and trucks made it possible to locate and pursue nomads. [NOTE: Resistance by desert dwellers against outsiders flared up occasionally after that, and led to guerilla warfare against the independent governments of Algeria, Mali, Mauritania and Niger as recently as 2003.]

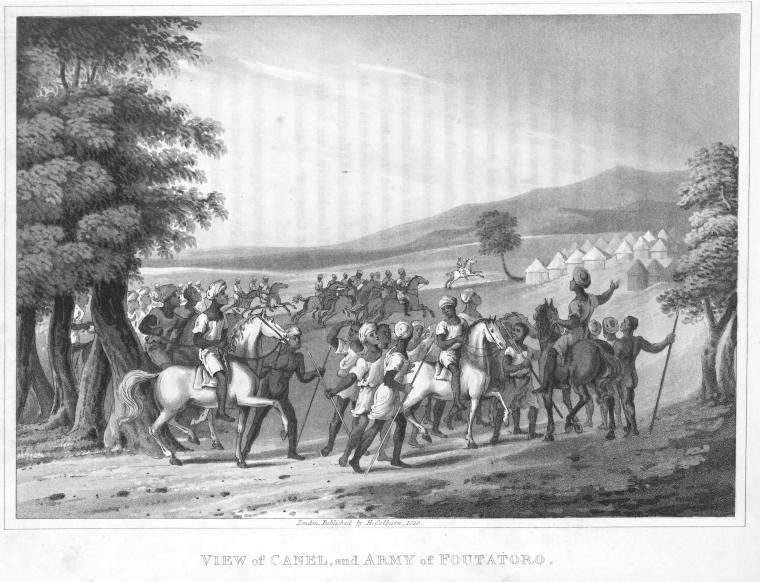

The first French initiative south of the Sahara took place along the Senegalese coast in 1843 under the leadership of Governor General Bouet Willaumez. He initiated a period of expansion by capturing the port of St. Louis at the mouth of the Senegal River and allowing privately-owned trading companies (mostly from Bordeaux) to handle the administration of the town. That ended in 1848 when the new French government of the Second Republic took over the local administration.

Imperial France gradually absorbed the territories of present-day Mauritania from the Senegal river area and upwards, starting in the late 19th century. In 1901, Xavier Coppolani took charge of the imperial

of strategic alliances with Zawiya tribes, and military pressure on the Hassane warrior nomads, he

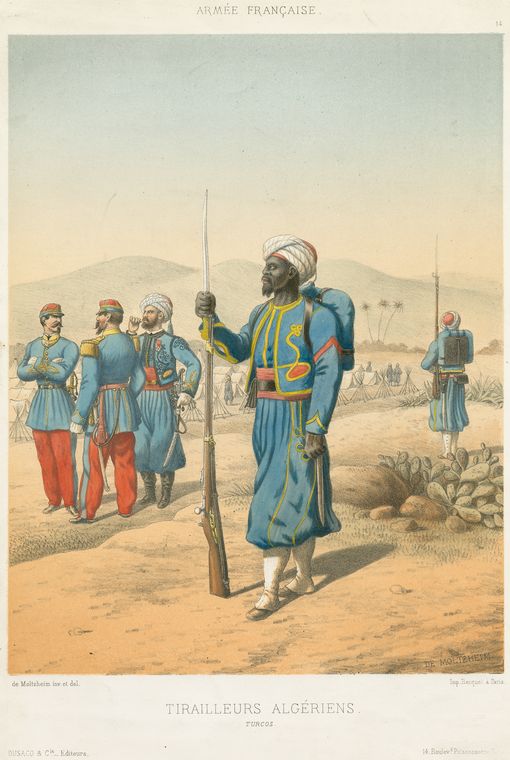

of strategic alliances with Zawiya tribes, and military pressure on the Hassane warrior nomads, he  managed to extend French rule over the Mauritanian emirates: Trarza, Brakna and Tagant quickly submitted to treaties with the colonial power. these are hat zouves but the trousers are more that of early french foreign legion, just change the headgear to a kepi.

managed to extend French rule over the Mauritanian emirates: Trarza, Brakna and Tagant quickly submitted to treaties with the colonial power. these are hat zouves but the trousers are more that of early french foreign legion, just change the headgear to a kepi.  (1903–04), but the northern emirate of Adrar held out longer, aided by the anticolonial rebellion (or

(1903–04), but the northern emirate of Adrar held out longer, aided by the anticolonial rebellion (or jihad) of shaykh Maa al-Aynayn. It was finally defeated militarily in 1912, and incorporated into the territory of Mauritania, which had been drawn up in 1904. Mauritania would subsequently form part of French West Africa, from 1920.

jihad) of shaykh Maa al-Aynayn. It was finally defeated militarily in 1912, and incorporated into the territory of Mauritania, which had been drawn up in 1904. Mauritania would subsequently form part of French West Africa, from 1920.French rule brought legal prohibitions against slavery, and an end to interclan warfare. During the colonial period, the population remained nomadic, but many sedentary peoples, whose ancestors had been expelled centuries earlier, began to trickle back into Mauritania. As the country gained independence in 1960, the capital city Nouakchott was founded at the site of a small colonial village, the Ksar, while 90% of the population was still nomadic.

The great Sahel droughts of the early 1970s caused massive problems in Mauritania. With independence, larger numbers of indigenous Sub-Saharan African peoples (Haalpulaar,

Soninke, and Wolof) entered

Soninke, and Wolof) entered SOUDAN

Consequently, the French exhausted an enormous amount of effort to claim it even though its economic value was small.

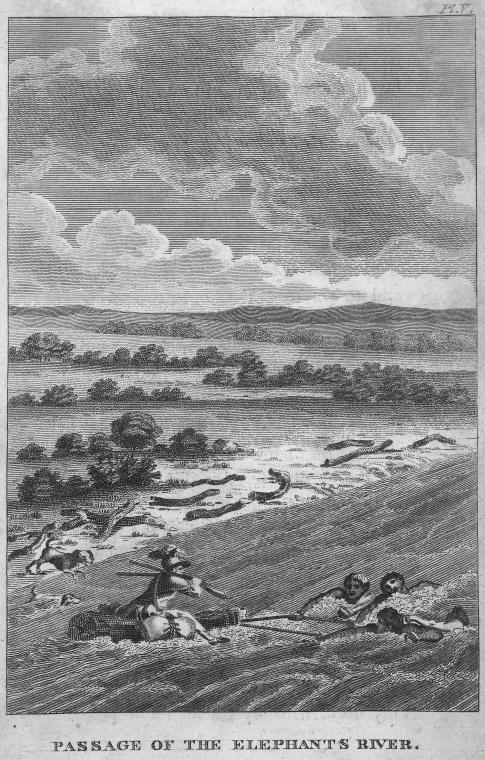

Prior to the 1850s, there was no French presence in the Soudan, although French explorer René Caillié passed through the area enroute to becoming the first European to return from Timbuktu in 1827-1828. In 1855 Faidherbe's troops began their advance towards the Upper Senegal River and built a fort at Médine, just below the Félou waterfall. Beyond that lay the empire of Ahmadu Tall with its capital at Ségou on the Niger River, and the empire of Samory Touré to the south east, with a capital at Sanankoro on the south side of the Niger River.

For a time, the French felt no need to formalize their presence, but as the British began to move inland from the mouth of the Niger River, the French began to fear that the British would seize the Middle Niger Valley and perhaps even reach the Upper Senegal Valley. That fear inspired a new episode of French aggression from 1876-1881 when Governor Brière de l'Isle authorized the construction of a railroad to the Niger and the creation of a military government of Haut Senegal et Niger (literally "Upper Senegal and Niger"), an area encompassing the modern states of Mali and Niger. [For more on this episode, see

The African empires offered resistance, so it took a decade for the French to conquer Ségou and almost twenty more years to defeat Samory. Resistance continued in the region around Lake Chad until 1900 and in the Sahara Desert until the 1930s. But by 1899, the French were able to place the Soudan under its own administration. IVORY COAST |  Samory Touré, leader of the last major anti-French resistance in the western Sudan Source: Gallieni, Deux campagnes ... |

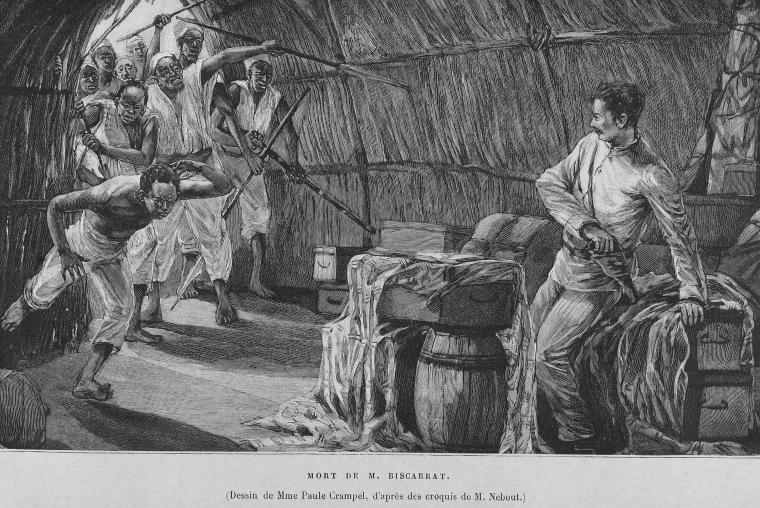

in 1894, they received help from newspaper correspondents who wrote unconfirmable accounts of African cruelty and barbaric acts. Since the only Europeans in a position to verify such reports were soldiers, the public never heard anyone defend African culture.

in 1894, they received help from newspaper correspondents who wrote unconfirmable accounts of African cruelty and barbaric acts. Since the only Europeans in a position to verify such reports were soldiers, the public never heard anyone defend African culture.

Dahomey was located between British Nigeria and German Togo along what Europeans called the "Slave Coast." French merchants began to trade there in the 17th century and in 1851, traders from Marseille signed a treaty of protection with King Guezo of Abomey which gave the French the right to build a permanent base on the coast at Ouidah. Another French trader named Daumas signed a similar treaty with King Sodji of Porto-Novo in 1863. Sodji's successor (Mekpu) tried to renounce the treaty with the French, but after he was defeated by a rival with French assistance in 1883, the French government became confident enough to make Porto Novo the capital of their possessions in the Gulf of Benin.

This was an affront to the kings of Abomey, who considered Porto Novo to be part of their realm. King Glegle of Abomey revoked his father's treaty in 1884 and the French sent a military expedition to restore their control. Glegle's death in 1889 placed his son Behanzin on the throne, and when Behanzin appeared likely to continue his father's opposition, the French responded by occupying Cotonou, a coastal village near the Abomey capital.

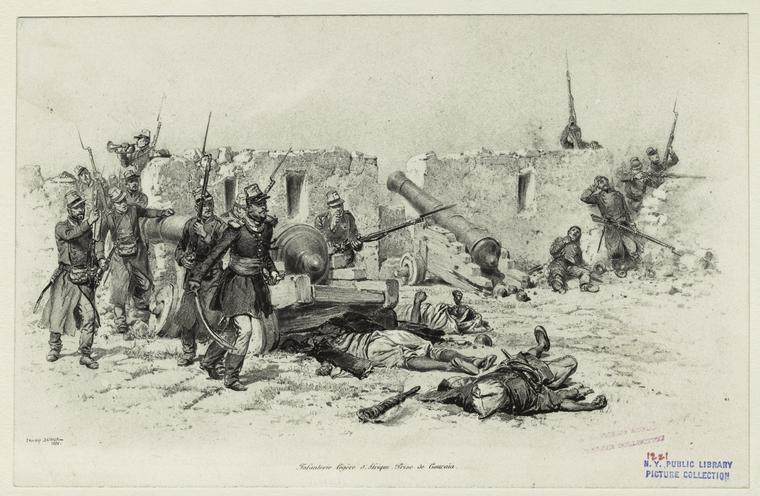

French newspapers helped drum up support for this effort with descriptions of human sacrifices that accompanied Behanzin's coronation. They also lavished attention on the troops who fought for the French including Foreign Legionnaires from Algeria and Tirailleurs (African troops in the French colonial army) from Senegal. The use of new technology such as the telegraph, repeating rifles, steam gunboats and machine guns also attracted interest, while reports of Dahomeyan "Amazons"-- military units composed entirely of women--titillated the French public's imagination.

The climax came in 1892 when an expedition led by a Senegalese mulatto, Colonel Alfred Amédée Dodds, marched from Ouidah to Abomey with four thousand soldiers. Following a series of battles in September and October, including several that pitted Legionnaires against Abomey's Amazons. the French reached the capital on November 17. King Behanzin had already fled, so the French amused themselves by collecting souvenirs including a white parasol decorated with human jawbones that received a great deal of attention from the press. Behanzin remained on the run until January 1894 when he was captured and exiled to Martinique. The French finished the campaign with 81 dead, 436 wounded and about 2,000 other casualties due to illness.

The 1892 French campaign in Dahomey affected European attitudes about Africa. It seemed to confirm that even a prosperous and well-organized state like Dahomey depended on practices--human sacrifice, women soldiers--that scandalized Victorian Europe. When the British launched the

Supporters of French expansion proposed both practical and idealistic goals. Practically speaking, French imperialists hoped to enhance the French economy to help pay the Prussian indemnity and to recover from the Great Depression of the 1870s. They also wanted to block British expansion in West Africa. On a more idealistic level, French imperialists envisioned the creation of a Greater French Empire that would promote what they considered to be the universal ideals of the Enlightenment. Coincidentally, such an empire was expected to extend and glorify French culture.

Philosophy professor Albert Memmi wrote in The Colonist and the Colonized (Boston, MA: Beacon Press, 1967) that the French had to have a grandiose concept of their own culture in order for expansion to succeed because the colonial system attracted only the most mediocre Europeans. Memmi argued that the colonizers were aware of their own mediocrity, so they bolstered their position with respect to colonized Africans by extolling the virtues of the French civilization. Coincidently, they viewed themselves as the best representatives of that civilization.

Writing about French politics in Jules Ferry and the Renaissance of French Imperialism, (London: King's Crown Press, 1944)., Thomas Power agreed with Memmi that the economic motive was secondary and argued that France's principle motivations were strategic and ideological. Power wrote that the economic arguments advanced by Jules Ferry to justify expansion, were created after the fact as a way to obtain financial support from the French legislature for projects that were already underway. [Power, 1944, 198.]

Once treaties were signed and French administration put in place, the French tried to convert Africans into citizens who understood the ideals of French civilization. To create citizens from uneducated Africans, the French employed a policy of assimilation which relied on white Frenchmen as teachers and models for African pupils whose object was to mimic French culture.

Not only did this serve the French government's need to demonstrate high moral purpose by "raising up the heathen," it also offered cost advantages. Africans who wanted to become French were not likely to revolt, so the French could do without expensive military garrisons to maintain order. Assimilated Africans also served in the lower levels of administration, saving the cost of bringing Europeans to Africa to fill their positions.

Viewed as an episode in French history, the conquest of Africa was a continuation of expansion of power that began under Louis XIII. In roughly three centuries, French governments extended their control from the Ile de France (surrounding Paris) to the North African coast. The conquest of West Africa was just the next step in this long process. From the perspective of other Europeans, France's expansion was seen as a form of opposition to Great Britain. The British felt threatened by it, the German prime miniser Bismarck encouraged it and the rest of the European nations tried to imitate it.

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)

TtHE ABOVE IS MY OWN CRESCENT CONVERSION OF THEIR 54MM FIGURE

TtHE ABOVE IS MY OWN CRESCENT CONVERSION OF THEIR 54MM FIGURE![View Smaller Image [Alfred Amedee Dodds.]](http://images.nypl.org/index.php?id=1249739&t=w)