Louis Lazare Hoche (24 June 1768 – 19 September 1797) was a French soldier who rose to be general of the Revolutionary army. Born of poor parents near Versailles, he enlisted at sixteen as a private soldier in the Gardes Françaises.

Born of poor parents near Versailles, he enlisted at sixteen as a private soldier in the Gardes Françaises.

He spent his entire leisure in earning extra pay by civil work, his object being to provide himself with books, and this love of study, which was combined with a strong sense of duty and personal courage, soon led to his promotion.

When the

Gardes françaises disbanded in 1789 he had reached the rank of corporal, and thereafter he served in various line regiments up to the time of his receiving a commission in 1792. In the defence of Thionville

in that year Hoche earned further promotion, and he served with credit in the operations of 1792 - 1793 on the northern frontier of France, including the Battle of Wissembourg. At the Battle of Neerwinden

(1793) he served as

aide-de-camp to General

le Veneur, and when Charles Dumouriez deserted to the Austrians, Hoche, along with le Veneur and others, fell under suspicion of treason. But after being kept under arrest and unemployed for some months he took part in the defence of Dunkirk,

and in the same year (1793) he was promoted successively

chef de brigade, general of brigade, and general of division. In October 1793 he was provisionally appointed to command the Army of the Moselle, and within a few weeks he was in the field at the head of his army in Lorraine. He lost his first battle at Kaiserslautern on 28–30 November 1793

against the Prussians, but even in the midst of the Reign of Terror the Committee of Public Safety retained Hoche in his command. Pertinacity and fiery energy, in their eyes, outweighed everything else, and Hoche soon showed that he possessed these qualities.

On 22 December 1793 he stormed the lines of Fröschweiler, and the representatives of the National Convention with his army at once added the Army of the Rhine to his sphere of command. On 26 December 1793 the French carried by assault the famous lines of Weissenburg, and Hoche pursued his success, sweeping the enemy before him to the middle Rhine in four days. He then put his troops into winter quarters.

Before the following campaign opened, he married Anne Adelaide Dechaux at Thionville (11 March 1794). But ten days later he was suddenly arrested, charges of treason having been preferred by Charles Pichegru, the displaced commander of the Army of the Rhine, and by his friends. Hoche escaped execution, however, though imprisoned in Paris until the fall of Maximilien Robespierre. Shortly after his release he was appointed to command against the Vendéans (21 August 1794).

He completed the work of his predecessors in a few months by the peace of

Jaunaye (15 February 1795), but soon afterwards the war was renewed by the Royalists. Hoche showed himself equal to the crisis and inflicted a crushing blow on the Royalist cause by defeating and capturing de Sombreuil's expedition at Quiberon and Penthièvre (16–21 July 1795). Thereafter, by means of mobile columns (which he kept under good discipline) he succeeded before the summer of 1796 in pacifying the whole of the west, which had for more than three years been the scene of a pitiless civil war.

caricatured the failure of Hoche's Irish expedition.

After this Hoche was appointed to organise and command the troops sent to assist the United Irishmen in their rebellion against British rule. A tempest, however, separated Hoche from the expedition, and after various adventures the whole fleet returned to Brest without having effected its purpose. Hoche was at once transferred to the Rhine frontier, where he defeated the Austrians at the Battle of Neuwied in April 1797, though operations were soon afterwards brought to an end by the Preliminaries of Leoben. Later in 1797 he was minister of war for a short period, but in this position he was surrounded by obscure political intrigues, and, finding himself the dupe of Paul Barras and technically guilty of violating the constitution, he quickly laid down his office, returning to his command on the Rhine frontier. But his health grew rapidly worse, and he died at Wetzlar on 19 September 1797 of consumption.

The belief spread that he had been poisoned, but the suspicion seems to have had no foundation. He was buried next to his friend François Marceau in a fort on the Rhine.

He is commemorated by a statue in Place Hoche, a gardened square not far from the main entrance to the Palace of Versailles. Another statue, the last major work by Jules Dalou, is in Quiberon, Brittany. In Les Invalides where Napoleon's tomb is enshrined, there is also a memorial to Hoche. A station on the Paris Metro is also called 'Hoche.'

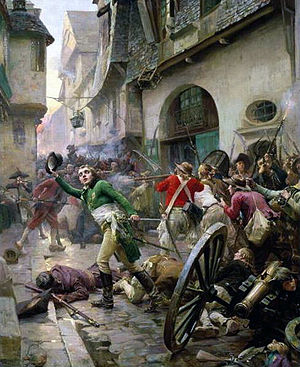

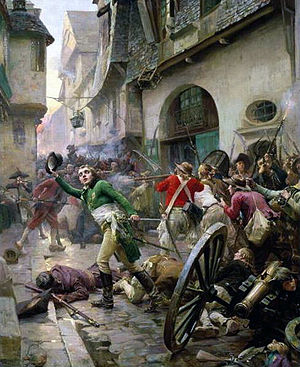

. Supported by the British, the French Royalists allied themselves with the Federalists and took

control of Toulon and Marseille. Faced with this uprising, the Revolutionary soldiers were forced to abandon Nîmes, Aix and Arles to the insurgents and fall back on Avignon. The inhabitants of Lambesc and Tarascon joined up with the rebels from Marseilles and together they headed for the Durance in order to march on Lyon, which had also revolted against the central government in Paris. The rebels hoped to destroy the Convention and put an end to the French Revolution.

Joseph Agricol Viala was a nephew of Agricol Moureau, a Jacobin from Avignon, editor of the Courrier d'Avignon and administrator of the département of Vaucluse. Joseph Agricol thus became commander of the "Espérance de la Patrie", a National Guard formed wholly of young men from Avignon.

On hearing news of the approach of the rebels from Marseille, at the start of July 1793, the Republican forces (mainly those from Avignon) gathered to stop the rebels crossing the Durance. Viala attached himself to the national guards from Avignon. Numerically inferior, their only solution was to cut the ropes of the bac de Bonpas under enemy fire. To do so, they had to cross a road completely exposed to rebel fire and behind which the Revolutionary forces had dug in. Despite its necessity, the Revolutionary forces were reluctant to undertake such a hazardous mission. According to accounts of the event, the 13-year-old Viala grabbed a hatchet, launched himself at the cable and started to cut it. He was the subject of several musket vollies and he was mortally wounded by a musket ball from one of them. One account stated:

| “ | In vain they tried to hold him back ; he braved the danger and no one could stop him from carrying out his audacious plan. He seized a sapper's hatchet, he shot at the enemy several times with his musket, then, despite the musket balls whistling around him he reached the river bank and, seizing his hatchet, struck the rope with vigour. Luck seemed to be with him at first, he nearly completed his perilous task without being hit, when at that moment a musket ball pierced his breast. He still managed to get up ; but he fell again with great force, crying out [in Provencal dialect] "M’an pas manqua ! Aquo es egaou ; more per la libertat." ("They haven't missed me! All is equal - I die for liberty."). Then he expired after the sublime farewell, without a complaint or regret. | ” |

Viala's attempt was unable to stop the rebels crossing the Durance, however. Nevertheless, it allowed the Revolutionary forces to carry out an ordered retreat without being able to pick up Viala's body. According to tradition, the Revolutionary soldier who heard Viala's last words tried to pick up the body but had to retreat before he could do so. This left the body to be insulted and mutilated by the advancing Royalists before they crossed the river. Learning of her son's death, Viala's mother said "Yes [...] he died for the fatherland

Hiram Berdan (September 6, 1824 – March 31, 1893) was an American engineer, inventor and military officer, world-renowned marksman,

Hiram Berdan (September 6, 1824 – March 31, 1893) was an American engineer, inventor and military officer, world-renowned marksman, the Berdan centerfire primer and numerous other weapons and accessoriesBerdan was born in Phelps, a small town in Ontario County, New York.

the Berdan centerfire primer and numerous other weapons and accessoriesBerdan was born in Phelps, a small town in Ontario County, New York. A mechanical engineer in New York City, he had been the top rifle shot in the country for fifteen years prior to the Civil War. He invented a repeating rifle and a patentedmusket ball before the war. He had also developed the first commercial gold amalgamation machine to separate gold from ore.

A mechanical engineer in New York City, he had been the top rifle shot in the country for fifteen years prior to the Civil War. He invented a repeating rifle and a patentedmusket ball before the war. He had also developed the first commercial gold amalgamation machine to separate gold from ore. He invented a reaper and a mechanical bakery. His inventions had brought him wealth and international fameIn the summer and fall of 1861, he was involved in the recruiting of eighteen companies, from eight states, which were formed into two sharpshooter regiments with the backing of General Winfield Scott and President Abraham Lincoln. Berdan was named as Colonel of the resultant 1st and 2nd U.S. Sharpshooters on November 30, 1861. His men, who had to pass rigorous marksmanship tests, were dressed in distinctive green uniforms and equipped with the most advanced long-range rifles featuring telescopic sights.

He invented a reaper and a mechanical bakery. His inventions had brought him wealth and international fameIn the summer and fall of 1861, he was involved in the recruiting of eighteen companies, from eight states, which were formed into two sharpshooter regiments with the backing of General Winfield Scott and President Abraham Lincoln. Berdan was named as Colonel of the resultant 1st and 2nd U.S. Sharpshooters on November 30, 1861. His men, who had to pass rigorous marksmanship tests, were dressed in distinctive green uniforms and equipped with the most advanced long-range rifles featuring telescopic sights. Even when assigned to a brigade, the regiments were usually detached for special assignments on the field of battle. They were frequently used for skirmish duty. Berdan fought at theSeven Days Bat.tles and Second Battle of Bull Run. In September 1862, his sharpshooters were at the Battle of Shepherdstown. Berdan commanded the 2nd Brigade, 3rd Division, 3rd Corps, Army of the Potomac in February and March 1863, then he commanded the 3rd Brigade at the Battle of Chancellorsville

Even when assigned to a brigade, the regiments were usually detached for special assignments on the field of battle. They were frequently used for skirmish duty. Berdan fought at theSeven Days Bat.tles and Second Battle of Bull Run. In September 1862, his sharpshooters were at the Battle of Shepherdstown. Berdan commanded the 2nd Brigade, 3rd Division, 3rd Corps, Army of the Potomac in February and March 1863, then he commanded the 3rd Brigade at the Battle of Chancellorsville

against the Prussians, but even in the midst of the Reign of Terror the Committee of Public Safety retained Hoche in his command. Pertinacity and fiery energy, in their eyes, outweighed everything else, and Hoche soon showed that he possessed these qualities.

against the Prussians, but even in the midst of the Reign of Terror the Committee of Public Safety retained Hoche in his command. Pertinacity and fiery energy, in their eyes, outweighed everything else, and Hoche soon showed that he possessed these qualities.