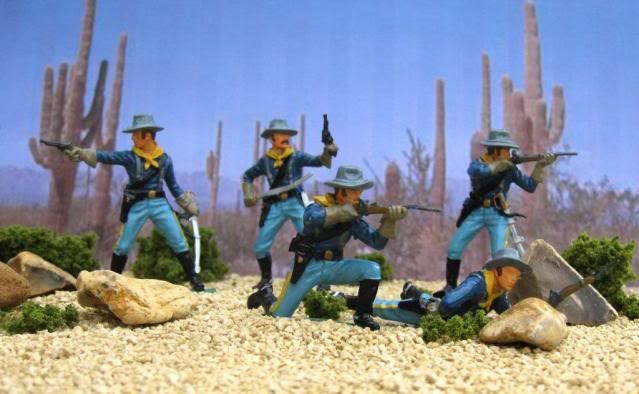

The Red River War was a military campaign launched by the United States Army in 1874 to remove the Comanche,

The Red River War was a military campaign launched by the United States Army in 1874 to remove the Comanche, Kiowa,Southern Cheyenne, and Arapaho

Kiowa,Southern Cheyenne, and Arapaho  Native American tribes from the Southern Plains and forcibly relocate them to reservations in Indian

Native American tribes from the Southern Plains and forcibly relocate them to reservations in Indian  Territory. Lasting only a few months, the war saw several army columns crisscross the Texas Panhandle

Territory. Lasting only a few months, the war saw several army columns crisscross the Texas Panhandle in an effort to locate, harass and capture highly mobile Indian bands. Most of the engagements were small skirmishes in which neither side suffered many casualties.

in an effort to locate, harass and capture highly mobile Indian bands. Most of the engagements were small skirmishes in which neither side suffered many casualties. The war wound down over the last few months of 1874 as fewer and fewer Indian bands had the strength and supplies to remain in the field. Though the last significantly sized group did not surrender until mid-1875,

The war wound down over the last few months of 1874 as fewer and fewer Indian bands had the strength and supplies to remain in the field. Though the last significantly sized group did not surrender until mid-1875, the war marked the end of free roaming Indian populations on the Southern Plains.Prior to the arrival of English American settlers on the Great Plains,

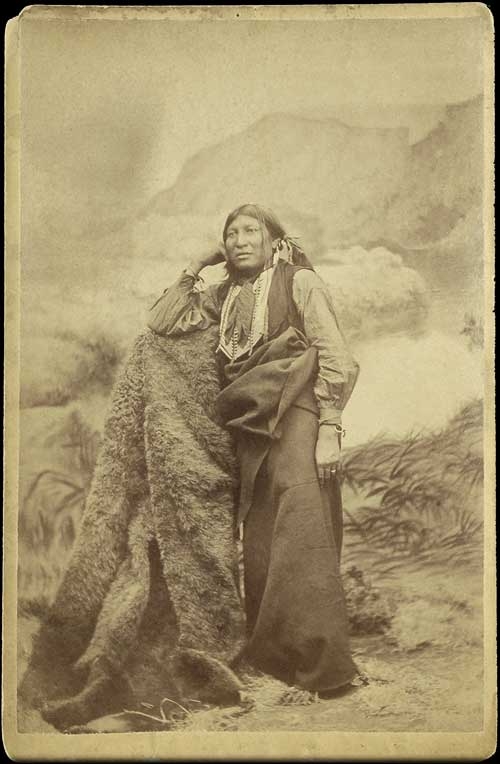

the war marked the end of free roaming Indian populations on the Southern Plains.Prior to the arrival of English American settlers on the Great Plains, the Southern Plains tribes had evolved into a nomadic pattern of existence. Beginning in the 1830s significant numbers of permanent settlements were established in what had previously been the exclusive territory of the Indigenous peoples of the Americas. Attacks, raids, and counter-raids occurred frequently. Prior to the Civil War, the U.S. Army was only sporadically involved in these frontier conflicts, manning forts but limited to a handful of larger expeditions due to manpower limitations. During the Civil War, the Regular Army withdrew almost completely and Indian raids increased dramatically. Texas, as part of the Confederate States of America, lacked the military resources to fight both the Union and the tribes.

the Southern Plains tribes had evolved into a nomadic pattern of existence. Beginning in the 1830s significant numbers of permanent settlements were established in what had previously been the exclusive territory of the Indigenous peoples of the Americas. Attacks, raids, and counter-raids occurred frequently. Prior to the Civil War, the U.S. Army was only sporadically involved in these frontier conflicts, manning forts but limited to a handful of larger expeditions due to manpower limitations. During the Civil War, the Regular Army withdrew almost completely and Indian raids increased dramatically. Texas, as part of the Confederate States of America, lacked the military resources to fight both the Union and the tribes.

After the war, the military began reasserting itself along the frontier. The Medicine Lodge Treaty, signed near present day Medicine Lodge, Kansas , in 1867, called for two reservations to be set aside in Indian Territory, one for the Comanche and Kiowa and one for the Southern Cheyenne and Arapaho. According to the treaty, the government would provide the tribes with housing, agricultural training, and food and other supplies. In exchange, the Indians agreed to cease raiding and attacking settlements. Dozens of chiefs endorsed the treaty and some tribal members moved voluntarily to the reservations, but it was never officially ratified and several groups of Indians still on the Plains did not attend the negotiations.

, in 1867, called for two reservations to be set aside in Indian Territory, one for the Comanche and Kiowa and one for the Southern Cheyenne and Arapaho. According to the treaty, the government would provide the tribes with housing, agricultural training, and food and other supplies. In exchange, the Indians agreed to cease raiding and attacking settlements. Dozens of chiefs endorsed the treaty and some tribal members moved voluntarily to the reservations, but it was never officially ratified and several groups of Indians still on the Plains did not attend the negotiations.

, in 1867, called for two reservations to be set aside in Indian Territory, one for the Comanche and Kiowa and one for the Southern Cheyenne and Arapaho. According to the treaty, the government would provide the tribes with housing, agricultural training, and food and other supplies. In exchange, the Indians agreed to cease raiding and attacking settlements. Dozens of chiefs endorsed the treaty and some tribal members moved voluntarily to the reservations, but it was never officially ratified and several groups of Indians still on the Plains did not attend the negotiations.

, in 1867, called for two reservations to be set aside in Indian Territory, one for the Comanche and Kiowa and one for the Southern Cheyenne and Arapaho. According to the treaty, the government would provide the tribes with housing, agricultural training, and food and other supplies. In exchange, the Indians agreed to cease raiding and attacking settlements. Dozens of chiefs endorsed the treaty and some tribal members moved voluntarily to the reservations, but it was never officially ratified and several groups of Indians still on the Plains did not attend the negotiations.

In 1870, a new technique for tanning buffalo hides became commercially available.

In response, commercial hunters began systematically targeting buffalo for the first time. Once numbering in the tens of millions, the buffalo population plummeted. By 1878 they would be all but extinct.

In response, commercial hunters began systematically targeting buffalo for the first time. Once numbering in the tens of millions, the buffalo population plummeted. By 1878 they would be all but extinct.

The destruction of the buffalo herds was a disaster for the Plains Indians, on and off the reservations. The entire nomadic way of life had been based around the animals. They were used for food, fuel and construction materials. Without abundant buffalo, the Southern Plains Indians had no means of self-support.

By the winter of 1873-1874, the Southern Plains Indians were in crisis. The reduction of the buffalo herds combined with increasing numbers of new settlers and more aggressive military patrols had put them in an unsustainable position.

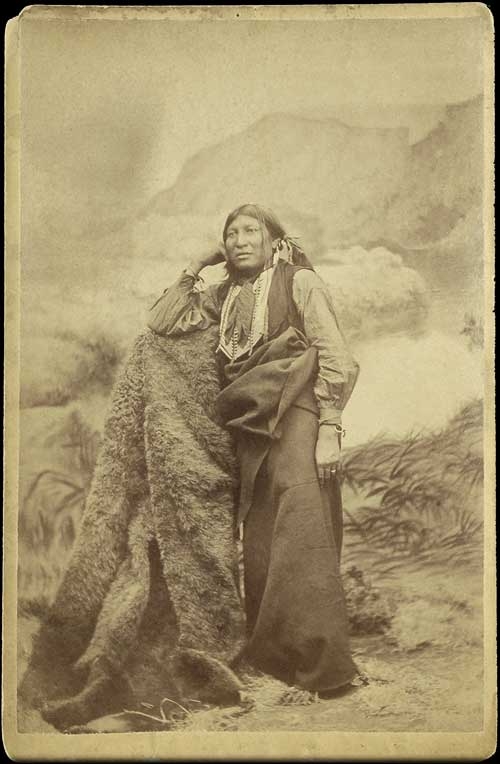

During the winter, a spiritual leader named Isa-tai (White Eagle) emerged among the Quahadi Band of Comanches. Isa-tai claimed to have the power to render himself and others invulnerable to their enemies, including to bullets, and was able to rally an enormous number of Indians for large raids. There was also a shift within the political structure of the Kiowa, bringing the war faction (influenced by the head chief Guipago,

(White Eagle) emerged among the Quahadi Band of Comanches. Isa-tai claimed to have the power to render himself and others invulnerable to their enemies, including to bullets, and was able to rally an enormous number of Indians for large raids. There was also a shift within the political structure of the Kiowa, bringing the war faction (influenced by the head chief Guipago, or Gui-pah-gho, sometimes known, by modern people, as Lone Wolf "the Elder" to prevent confusion with Mamay-dayte, later named Lone Wolf "the Younger" i

or Gui-pah-gho, sometimes known, by modern people, as Lone Wolf "the Elder" to prevent confusion with Mamay-dayte, later named Lone Wolf "the Younger" i nto a greater position of influence than they had held previously.

nto a greater position of influence than they had held previously.

(White Eagle) emerged among the Quahadi Band of Comanches. Isa-tai claimed to have the power to render himself and others invulnerable to their enemies, including to bullets, and was able to rally an enormous number of Indians for large raids. There was also a shift within the political structure of the Kiowa, bringing the war faction (influenced by the head chief Guipago,

(White Eagle) emerged among the Quahadi Band of Comanches. Isa-tai claimed to have the power to render himself and others invulnerable to their enemies, including to bullets, and was able to rally an enormous number of Indians for large raids. There was also a shift within the political structure of the Kiowa, bringing the war faction (influenced by the head chief Guipago, or Gui-pah-gho, sometimes known, by modern people, as Lone Wolf "the Elder" to prevent confusion with Mamay-dayte, later named Lone Wolf "the Younger" i

or Gui-pah-gho, sometimes known, by modern people, as Lone Wolf "the Elder" to prevent confusion with Mamay-dayte, later named Lone Wolf "the Younger" i nto a greater position of influence than they had held previously.

nto a greater position of influence than they had held previously.

On 27 June 1874, Isa-tai and Comanche chief Quanah Parker led approximately 250 warriors in an attack on a small outpost of buffalo hunters in the Texas Panhandle calledAdobe Walls.  The encampment consisted of just a few buildings and was occupied by only twenty-eight men and one woman. Though a few whites were killed in the opening moments of the Second Battle of Adobe Walls (the first had been in 1864), the majority were able to barricade themselves indoors and hold off the attack. Using large caliber buffalo guns, the hunters could fire on the warriors from much greater range than the Indians had expected, and the attack failed.

The encampment consisted of just a few buildings and was occupied by only twenty-eight men and one woman. Though a few whites were killed in the opening moments of the Second Battle of Adobe Walls (the first had been in 1864), the majority were able to barricade themselves indoors and hold off the attack. Using large caliber buffalo guns, the hunters could fire on the warriors from much greater range than the Indians had expected, and the attack failed.

The encampment consisted of just a few buildings and was occupied by only twenty-eight men and one woman. Though a few whites were killed in the opening moments of the Second Battle of Adobe Walls (the first had been in 1864), the majority were able to barricade themselves indoors and hold off the attack. Using large caliber buffalo guns, the hunters could fire on the warriors from much greater range than the Indians had expected, and the attack failed.

The encampment consisted of just a few buildings and was occupied by only twenty-eight men and one woman. Though a few whites were killed in the opening moments of the Second Battle of Adobe Walls (the first had been in 1864), the majority were able to barricade themselves indoors and hold off the attack. Using large caliber buffalo guns, the hunters could fire on the warriors from much greater range than the Indians had expected, and the attack failed.

A second engagement involved the Kiowa and took place in Texas. Warriors led by Lone Wolf attacked a patrol of Texas Rangers in July. The Lost Valley fight saw light casualties on both sides, but it served to raise tensions along the frontier and push the Army into an aggressive response.

The explosion of violence took the government by surprise. The "peace policy" of the Grant Administration was deemed a failure, and the Army was authorized to subdue the Southern Plains tribes with whatever force necessary. At this time, roughly 1,800 Cheyennes, 2,000 Comanches, and 1,000 Kiowas remained at large. Combined, they mounted about 1,200 warriors.

General Phillip Sheridan ordered five army columns to converge on the general area of the Texas Panhandle and specifically upon the upper tributaries of the Red River . The strategy was to deny the Indians any safe haven and attack them unceasingly until they went permanently to the reservations.

. The strategy was to deny the Indians any safe haven and attack them unceasingly until they went permanently to the reservations.

General Phillip Sheridan ordered five army columns to converge on the general area of the Texas Panhandle and specifically upon the upper tributaries of the Red River

. The strategy was to deny the Indians any safe haven and attack them unceasingly until they went permanently to the reservations.

. The strategy was to deny the Indians any safe haven and attack them unceasingly until they went permanently to the reservations.

Three of the five columns were under the command of Colonel Ranald S. Mackenzie. The Tenth Cavalry, under Lieutenant Colonel John W. Davidson, came due west from Fort Sill.  The Eleventh Infantry, under Lieutenant Colonel George P. Buell,

The Eleventh Infantry, under Lieutenant Colonel George P. Buell, moved northwest from Fort Griffin.

moved northwest from Fort Griffin. Mackenzie himself led the Fourth Cavalry north from Fort Concho.

Mackenzie himself led the Fourth Cavalry north from Fort Concho.

The Eleventh Infantry, under Lieutenant Colonel George P. Buell,

The Eleventh Infantry, under Lieutenant Colonel George P. Buell, Mackenzie himself led the Fourth Cavalry north from Fort Concho.

Mackenzie himself led the Fourth Cavalry north from Fort Concho.

The fourth column, consisting of the Sixth Cavalry and Fifth Infantry, was commanded by Colonel Nelson A. Miles and came south from Fort Dodge. The fifth column, the Eighth Cavalry commanded by Major William R. Price, a total of 225 officers and men, plus six Indian scouts and two guides originating from Fort Union ,marched east via Fort Bascom in New Mexico.[The plan called for the converging columns to maintain a continuous offensive until a decisive defeat had been inflicted on the Indians.

,marched east via Fort Bascom in New Mexico.[The plan called for the converging columns to maintain a continuous offensive until a decisive defeat had been inflicted on the Indians.

,marched east via Fort Bascom in New Mexico.[The plan called for the converging columns to maintain a continuous offensive until a decisive defeat had been inflicted on the Indians.

,marched east via Fort Bascom in New Mexico.[The plan called for the converging columns to maintain a continuous offensive until a decisive defeat had been inflicted on the Indians.

As many as twenty engagements took place across the Texas Panhandle. The Army, consisting entirely of soldiers and scouts, sought to engage the Indians at any opportunity. The Indians, traveling with women, children and elderly, mostly attempted to avoid them. When the two did encounter one another, the Indians usually tried to escape before the Army could force them to surrender. However, even a successful escape could be disastrously costly if horses, food and equipment had to be left behind. By contrast, the Army and its Indian scouts had access to essentially limitless supplies and equipment, they frequently burned anything they captured from retreating Indians, and were capable of continuing operations indefinitely. The war continued throughout the fall of 1874, but increasing numbers of Indians were forced to give up and head for Fort Sill to enter the reservation system.

Main article: Battle of Palo Duro CanyonThe largest Army victory came when Mackenzie found a large village of Comanche, Kiowa and Cheyenne, including their horses and winter food supply, in upper Palo Duro Canyon. At dawn on September 28, Mackenzie's troops attacked down a steep canyon wall. The Indians were caught by surprise and didn't have time to gather their horses or supplies before retreating. Sergeant John Charlton wrote of the battle:

- "The warriors held their ground for a time, fighting desperately to cover the exit of their squaws and pack animals, but under the persistent fire of the troops they soon began falling back."

Only four Indians were killed, but the loss was devastating. Mackenzie's men burned over 450 lodges and destroyed countless pounds of buffalo meat. They also took 1,400 horses, most of which were subsequently shot to prevent the Indians from recapturing them.

Except for its unusually large size, the Battle of Palo Duro Canyon was typical of the war. Most encounters produced few or no casualties, but the Indians could not afford the constant loss of food and mounts. Even if it escaped immediate danger, an Indian band that found itself on foot and out of food generally had no choice but to give up and head for the reservation.

The Red River War officially ended in June 1875 when Quanah Parker and his band of Quahadi Comanche entered Fort Sill and surrendered; they were the last large roaming band of southwestern Indians. Combined with the extermination of the buffalo, the war left the Texas Panhandle permanently open to settlement by farmers and ranchers[ It was the final military defeat of the once powerful Southern Plains tribes and brought an end to the Texas–Indian Wars.

of around $20,000. Considering that trio as the root of the Wild Bunch, we can fold in later crimes in which they participated.

of around $20,000. Considering that trio as the root of the Wild Bunch, we can fold in later crimes in which they participated.

The gang dissolved after Fred and Bill died during an 1893 attempt on the Farmers and Merchants Bank in Delta, Colorado.

The gang dissolved after Fred and Bill died during an 1893 attempt on the Farmers and Merchants Bank in Delta, Colorado.

On April 21, 1897, Butch, Lay and perhaps Meeks and Joe Walker stole a $9,860 mine payroll in Castle Gate, Utah.

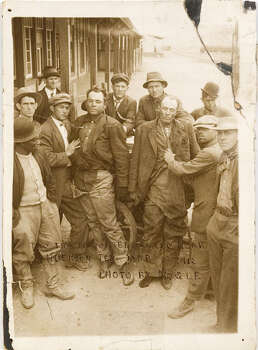

On April 21, 1897, Butch, Lay and perhaps Meeks and Joe Walker stole a $9,860 mine payroll in Castle Gate, Utah. Butte County Bank in Belle Fourche, South Dakota. Tom O’Day

Butte County Bank in Belle Fourche, South Dakota. Tom O’Day  was caught hiding in a saloon privy. His cohorts included Walt Punteney, George “Flat Nose” Currie, Harvey Logan

was caught hiding in a saloon privy. His cohorts included Walt Punteney, George “Flat Nose” Currie, Harvey Logan  (making his debut in the Wild Bunch) and Sundance. Butch may have participated, but it’s doubtful. The bungling bandits got $97. O’Day was tried and acquitted; Punteney was arrested, but the charges were dropped.

(making his debut in the Wild Bunch) and Sundance. Butch may have participated, but it’s doubtful. The bungling bandits got $97. O’Day was tried and acquitted; Punteney was arrested, but the charges were dropped.

escaping with $450. Two other men were tried for the holdup and acquitted.

escaping with $450. Two other men were tried for the holdup and acquitted. of several hundred dollars. The Wild Bunch holding up saloons? Maybe not. (Unsolved crimes are

of several hundred dollars. The Wild Bunch holding up saloons? Maybe not. (Unsolved crimes are  often attributed to famous outlaws.) Three local cowboys were tried for the robbery and acquitted.

often attributed to famous outlaws.) Three local cowboys were tried for the robbery and acquitted.

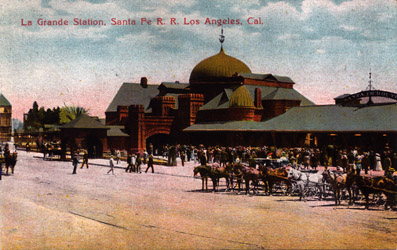

on May 14, 1897, taking upwards of $42,000. Reinforced by Tom’s brother, Sam, and possibly Bruce “Red” Weaver, they robbed the Gulf, Colorado & Santa Fe No. 1

on May 14, 1897, taking upwards of $42,000. Reinforced by Tom’s brother, Sam, and possibly Bruce “Red” Weaver, they robbed the Gulf, Colorado & Santa Fe No. 1 on September 3, 1897, of several thousand dollars. Weaver was later tried for the crime and acquitted.

on September 3, 1897, of several thousand dollars. Weaver was later tried for the crime and acquitted.

mortally wounded; Lay was wounded and later captured; and Carver escaped. (Some say the third bandit was Harvey Logan, not Carver.)

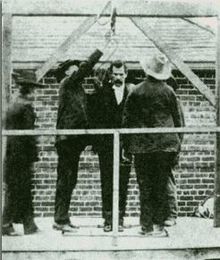

mortally wounded; Lay was wounded and later captured; and Carver escaped. (Some say the third bandit was Harvey Logan, not Carver.) . On August 16, 1899, he attempted holding up the Colorado & Southern No. 1 near Folsom, New Mexico, but was shot, captured, tried, convicted and hanged.

. On August 16, 1899, he attempted holding up the Colorado & Southern No. 1 near Folsom, New Mexico, but was shot, captured, tried, convicted and hanged.

of between $55.40 (the initial account) and $55,000 (a later report). The five bandits included Butch and probably Sundance and Harvey Logan. Also suspected were Ben Kilpatrick, Tom Welch and Billy Rose. Tipton was the first crime in which Butch and Sundance are generally agreed to have teamed up. They were just six months from fleeing the country.

of between $55.40 (the initial account) and $55,000 (a later report). The five bandits included Butch and probably Sundance and Harvey Logan. Also suspected were Ben Kilpatrick, Tom Welch and Billy Rose. Tipton was the first crime in which Butch and Sundance are generally agreed to have teamed up. They were just six months from fleeing the country. collecting between $32 and $40,000. Sundance, Carver and Logan are thought to have participated, but some suspected local miscreants, and others called it an inside job. The bank’s head cashier, George Nixon, at various times agreed and disagreed that Butch was present. A few years later, a newspaper recounted a conversation in which Sundance supposedly disclosed that he, Butch and Carver were responsible. Stories that the bandits had camped near Winnemucca as early as September 9, however, have prompted researchers to question whether Butch could have been at both Tipton and Winnemucca, 600 miles apart.

collecting between $32 and $40,000. Sundance, Carver and Logan are thought to have participated, but some suspected local miscreants, and others called it an inside job. The bank’s head cashier, George Nixon, at various times agreed and disagreed that Butch was present. A few years later, a newspaper recounted a conversation in which Sundance supposedly disclosed that he, Butch and Carver were responsible. Stories that the bandits had camped near Winnemucca as early as September 9, however, have prompted researchers to question whether Butch could have been at both Tipton and Winnemucca, 600 miles apart. Kilpatrick and Logan went to prison for passing bank notes from the holdup, and Hanks died the next year in a confrontation with authorities in Texas.

Kilpatrick and Logan went to prison for passing bank notes from the holdup, and Hanks died the next year in a confrontation with authorities in Texas.

Parachute, Colorado,

Parachute, Colorado, on June 7, 1904. Wounded and cornered, Logan committed suicide. The list of possible accomplices is long, but George Kilpatrick (Ben’s brother) and Dan Sheffield are high on it. George is thought to have been mortally wounded, although his body was never found.

on June 7, 1904. Wounded and cornered, Logan committed suicide. The list of possible accomplices is long, but George Kilpatrick (Ben’s brother) and Dan Sheffield are high on it. George is thought to have been mortally wounded, although his body was never found.

on March 13, 1912. Quick-witted Wells Fargo messenger David Trousdale fatally bludgeoned Kilpatrick with an ice mallet, borrowed his rifle, and dropped Beck.

on March 13, 1912. Quick-witted Wells Fargo messenger David Trousdale fatally bludgeoned Kilpatrick with an ice mallet, borrowed his rifle, and dropped Beck. were family based. All the bandits put together committed or attempted more than two dozen

were family based. All the bandits put together committed or attempted more than two dozen  holdups. They probably didn’t do some they’ve been blamed for, and they probably pulled others they’ve never been accused of.

holdups. They probably didn’t do some they’ve been blamed for, and they probably pulled others they’ve never been accused of.

, under the alias William T. Phillips until his death in 1937.

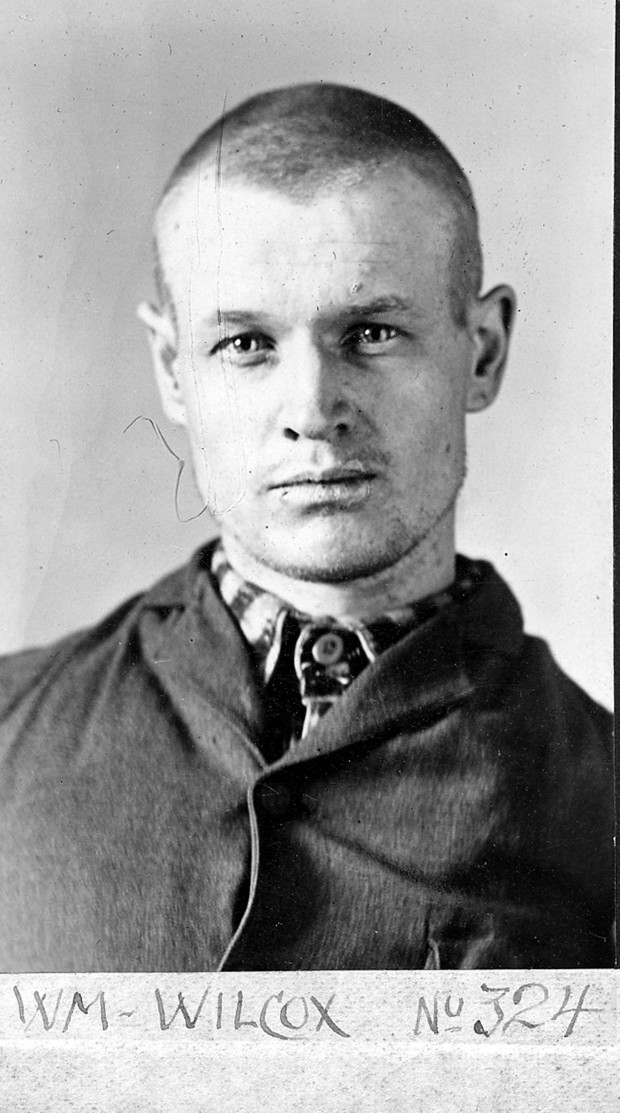

, under the alias William T. Phillips until his death in 1937. Wilcox, he realized, was actually the same person as Phillips, and Phillips was not Cassidy.

Wilcox, he realized, was actually the same person as Phillips, and Phillips was not Cassidy.