Saturday, 26 May 2012

Friday, 25 May 2012

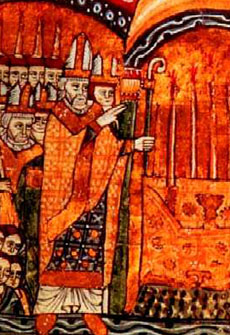

The hermit

Peter the Hermit, a priest of Amiens,

who may, as Anna Comnena says, have attempted to go on a pilgrimage to Jerusalem before 1096, and have been prevented by the Turks from reaching his destination. It is uncertain whether he was present at Pope Urban II's

who may, as Anna Comnena says, have attempted to go on a pilgrimage to Jerusalem before 1096, and have been prevented by the Turks from reaching his destination. It is uncertain whether he was present at Pope Urban II's great sermon at Clermont in 1095; but it is certain that he was one of the preachers of the crusade in France after that sermon, and his own experience may have helped to give fire to his eloquence. He soon leapt into fame as an emotional revivalist preacher: his very ass became an object of popular adoration; and thousands of peasants eagerly took the cross at his bidding. The crusade of the pauperes, which forms the first act in the first crusade, was his work; and he himself led one of the five sections of the pauperes to Constantinople, starting from Cologne in April, and arriving at Constantinople at the end of July 1096. Here he joined the only other section which had succeeded in reaching Constantinople -- that of Walter the Penniless; and with the joint forces, which had made themselves a nuisance by pilfering, he crossed to the Asiatic shore in the beginning of August. In spite of his warnings, the pauperes began hostilities against the Turks; and Peter returned to Constantinople, either in despair at their recklessness, or in the hope of procuring supplies. In his absence the army was cut to pieces by the Turks; and he was left in Constantinople without any followers, during the winter of 1096-97, to wait for the coming of the princes. He joined himself to their ranks in May 1097, with a little following which he seems to have collected, and marched with them through Asia Minor to Jerusalem. But he played a very subordinate part in the history of the first crusade. He appears, in the beginning of 1098, as attempting to escape from the privations of the siege of Antioch -- showing himself, as Guibert of Nogent says, a "fallen star." In the middle of the year he was sent by the princes to invite Kerbogha to settle all differences by a duel; and in 1099 he appears as treasurer of the alms at the siege of Arca (March), and as leader of the supplicatory processions in Jerusalem which preceded the battle of Ascalon (August). At the end of the year he went to Laodicea, and sailed from there for the West. From this time he disappears; but Albert of Aix records that he died in 1115, as prior of a church of the Holy Sepulchre which he had founded in France.

great sermon at Clermont in 1095; but it is certain that he was one of the preachers of the crusade in France after that sermon, and his own experience may have helped to give fire to his eloquence. He soon leapt into fame as an emotional revivalist preacher: his very ass became an object of popular adoration; and thousands of peasants eagerly took the cross at his bidding. The crusade of the pauperes, which forms the first act in the first crusade, was his work; and he himself led one of the five sections of the pauperes to Constantinople, starting from Cologne in April, and arriving at Constantinople at the end of July 1096. Here he joined the only other section which had succeeded in reaching Constantinople -- that of Walter the Penniless; and with the joint forces, which had made themselves a nuisance by pilfering, he crossed to the Asiatic shore in the beginning of August. In spite of his warnings, the pauperes began hostilities against the Turks; and Peter returned to Constantinople, either in despair at their recklessness, or in the hope of procuring supplies. In his absence the army was cut to pieces by the Turks; and he was left in Constantinople without any followers, during the winter of 1096-97, to wait for the coming of the princes. He joined himself to their ranks in May 1097, with a little following which he seems to have collected, and marched with them through Asia Minor to Jerusalem. But he played a very subordinate part in the history of the first crusade. He appears, in the beginning of 1098, as attempting to escape from the privations of the siege of Antioch -- showing himself, as Guibert of Nogent says, a "fallen star." In the middle of the year he was sent by the princes to invite Kerbogha to settle all differences by a duel; and in 1099 he appears as treasurer of the alms at the siege of Arca (March), and as leader of the supplicatory processions in Jerusalem which preceded the battle of Ascalon (August). At the end of the year he went to Laodicea, and sailed from there for the West. From this time he disappears; but Albert of Aix records that he died in 1115, as prior of a church of the Holy Sepulchre which he had founded in France. Legend has made Peter the Hermit the author and originator of the first crusade. It has told how, in an early visit to Jerusalem, before 1096, Jesus Christ appeared to him in the Church of the Sepulchre, and bade him preach the crusade. The legend is without any basis in fact, though it appears in the pages of William of Tyre. Its origin is, however, a matter of some interest. Von Sybel, in his Geschichte des ersten Kreuzzuges, suggests that in the camp of the pauperes (which existed side by side with that of the knights, and grew increasingly large as the crusade told more and more heavily in its progress on the purses of the crusaders) some idolization of Peter the Hermit had already begun, during the first crusade, parallel to the similar glorification of Godfrey by the Lorrainers. In this idolization Peter naturally became the instigator of the crusade, just as Godfrey became the founder of the kingdom of Jerusalem and the legislator of the assizes. This version of Peter's career seems as old as the Chanson des chétifs, a poem which Raymond of Antioch caused to be composed in honor of the Hermit and his followers soon after 1130. It also appears in the pages of Albert of Aix, who wrote somewhere about 1130; and from Albert it was borrowed by William of Tyre. The whole legend of Peter is an excellent instance of the legendary amplification of the first crusade -- an amplification which, beginning during the crusade itself, in the "idolizations" of the different camps (idola castrorum, if one may pervert Bacon), soon developed into a regular saga. This saga found its most piquant beginning in the Hermit's vision at Jerusalem, and there it accordingly began -- alike in Albert, followed by William of Tyre and in the Chanson des chétifs, followed by the later Chanson d'Antioche.

On reaching Asia, the apostle of the crusade found himself in command of a hundred thousand men; for at Constantinople, besides being joined by Walter, he had been reinforced by large bodies of Germans and Italians. All these were as enthusiastic and refractory as the crusaders from France, and never had men to perform a more difficult duty than had devolved upon the Hermit and the Knight. Their united cfibrts failed to preserve anything like discipline; and while on the plains bordering the gulf of Nicomedia, their camp became the scene of discord and disorder.

At length the crusaders of the Germany and Italian States came to daggers' drawn with those from France about plunder. Not relishing the superiority assumed by the boastful Frenchmen, the Germans and Italians elected a leader, and, leaving the camp, advanced towards Nice. Arriving before a fort, they commenced an assault; and, entering, sword in hand, slaughtered the garrison. Though without means of subsistence or defence, they boldly took possession, and displayed their standard. Their audacity was not, of course, long left unpunished. A Turkish army soon appeared; and the Germans and Italians, unprepared for resistance, fell victims to their temerity.

When news of this disaster reached the camp of the crusaders, the French, forgetting their feud, vowed to be the avengers of the Germans and Italians, and gave way to extraordinary excitement. Peter had repaired in disgust to Constantinople; but Walter did all he could to prevent fatal consequences.

"The Germans and Italians are unworthy of the sacrifice you would make," said the penniless Knight to those who had constituted themselves ringleaders of the mob. "These men have fallen victims to their own imprudence; and it is our duty to avoid their example."

"That,'' cried the ringleaders in chorus," is the language of a man who lacks courage."

"I tell you," answered Walter, with a gesture of indignation, "that the enterprise you propose promises nothing but ruin. But have your own way. I cannot sanction your folly, but I will share your fate."

"God wills it," cried the ringleaders, as they rushed from the tent and roused the mob to arms.

The man who at this period figured as Sultan of Nice was not one whom the crusaders, if they had been discreet would have rashly defied. Reared in the midst of civil strife, and accustomed in his youth to adversity, he was dauntless in defeat and calm in victory. His foes named him with respect; and his friends, with pride, surnamed him "The Lion." On this occasion, he was under no serious apprehension; for he was aware of the imprudence of the pilgrims, and quite prepared to avail himself of its result.

Little dreaming of the reception with which they were to meet, the crusaders placed themselves in marching order; and Walter the Penniless, groaning in spirit, and leaving the women and children, and old men in the camp, led the van towards Nice. For a time he pursued his way without interruption. Suddenly, however, horns and drums heralded an attack; Saracens, with white turbans, green caftans, and long spears came in sight; and, on reaching a plain at the base of a mountain, the peasant-pilgrims found themselves face to face with countless foes. Walter halted, formed his men, and did all that a brave and sagacious leader could do under such circumstances; but his skill was exerted in vain. Surrounded on all sides by superior numbers, and shrinking from the peril they had defied, the crusaders lost heart and energy. At first, indeed, the conflict was fierce, and the carnage fearful. But ere long every hope expired \ and, with

Christian blood flowing around him like water, Walter fell in the midst of his foes, transfixed with arrows and covered with wounds.

Nor did the camp where the women and children had been left long escape. While the priests were performing mass, the victorious Turks suddenly appeared; and the unfortunate women and children were either put to death or carried into captivity. No one, however, escaped to tell the tale of horror.

It was only by accident that Christendom learned the catastrophe that had befallen the wreck of the first army of the cross. A soldier escaping to Constantinople carried to Peter the Hermit tidings of the fate of his comrades; and on the plain where the Sultan of Nice fought with Walter the Penniless, a quantity of human bones heaped confusedly together, remained a melancholy monument of the carnage of the peasant-pilgrims.

Tuesday, 22 May 2012

Monday, 21 May 2012

leningrad by crescent

The capture of Leningrad was one of three strategic goals in the German Operation Barbarossa and the main target of Army Group North. The strategy was motivated by Leningrad's political status as the former capital of Russia and the symbolic capital of the Russian Revolution, its military importance as a main base of the Soviet Baltic Fleet and its industrial strength, housing numerous arms factories. By 1939 the city was responsible for 11% of all Soviet industrial output.

It has been reported that Adolf Hitler was so confident of capturing Leningrad that he had the invitations to the victory celebrations to be held in the city's Hotel Astoria already printed.The ultimate fate of the city was uncertain in German plans, which ranged from renaming the city to Adolfsburg and

making it the capital of the new Ingermanland province of the Reich in Generalplan Ost, to razing it to the ground and giving areas north of the River Neva to the FinnsFor everyone who lives in St. Petersburg the the Siege of Leningrad is a painful memory -Less than two and a half months after the Soviet Union was attacked by Nazi Germany, German troops were already approaching Leningrad. The Red Army was outflanked and on September 8 1941 the Germans had fully encircled Leningrad and the siege began. The siege lasted for a total of 900 days, from September 8 1941 until January 27 1944. The city's almost 3 million civilians (including about 400,000 children) refused to surrender and endured rapidly increasing hardships in the encircled city. Food and fuel stocks were limited to a mere 1-2 month supply, public transport was not operational and by the winter of 1941-42 there was no heating, no water supply, almost no electricity and very little food. In January 1942 in the depths of an unusually cold winter, the city's food rations reached an all time low of only 125 grams (about 1/4 of a pound) of bread per person per day. In just two months, January and February of 1942, 200,000 people died in Leningrad of cold and starvation. Despite these tragic losses and the inhuman conditions the city's war industries still continued to work and the city did not surrender

making it the capital of the new Ingermanland province of the Reich in Generalplan Ost, to razing it to the ground and giving areas north of the River Neva to the FinnsFor everyone who lives in St. Petersburg the the Siege of Leningrad is a painful memory -Less than two and a half months after the Soviet Union was attacked by Nazi Germany, German troops were already approaching Leningrad. The Red Army was outflanked and on September 8 1941 the Germans had fully encircled Leningrad and the siege began. The siege lasted for a total of 900 days, from September 8 1941 until January 27 1944. The city's almost 3 million civilians (including about 400,000 children) refused to surrender and endured rapidly increasing hardships in the encircled city. Food and fuel stocks were limited to a mere 1-2 month supply, public transport was not operational and by the winter of 1941-42 there was no heating, no water supply, almost no electricity and very little food. In January 1942 in the depths of an unusually cold winter, the city's food rations reached an all time low of only 125 grams (about 1/4 of a pound) of bread per person per day. In just two months, January and February of 1942, 200,000 people died in Leningrad of cold and starvation. Despite these tragic losses and the inhuman conditions the city's war industries still continued to work and the city did not surrender

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)