Britain is a country blessed with a wealth of history; from ancient Celtic barrows, through to Roman villas and imposing medieval fortresses, and on to the architectural splendour of the Victorian era. From Stonehenge to St Albans Abbey, from Windsor Castle to Westminster, our ancestors have left us all with a precious legacy; a huge array of buildings – many of them open to the public – which serve as a timeless testimony to our extensive heritage.

When walking around such places, places which have survived and persisted through generation after generation of Britons, it is easy to feel that these solid rock-hewn castles and towering cathedrals are impregnable; that they will simply always be there as a constant national bequest for future generations to inherit.

But history does not stand still, and our ancient fortresses – built to withstand the enemies of their day – are not always proof against the inevitable march of progress. The occupying Romans desecrated centuries-old Druidic temples, Cromwell destroyed castles across the land upon gaining power and Henry VIII obliterated a wealth of ancient abbeys and monasteries. Of course, such destruction has always been cyclical, part of our historical evolution, and for every desecrated temple we have, in the fullness of time, gained a Roman villa. For every devastated castle a magnificent country manor has been constructed.

History, and the buildings which remain as its legacy, is always developing, always evolving. However, in more modern times – from the industrialisation of the Victorian era through to the consumerism of the late twentieth and early twenty-first centuries – a new type of evolution has developed: one which uses up our heritage as a resource, without necessarily replacing it.

As the United Kingdom gained in prosperity at the turn of the Nineteenth century, two key social and political developments occurred. Firstly the country moved from a hierarchical structure, based upon a wide divide between the ruling classes and the masses, to become a capitalist system, based upon the forces of trade and economics. Economy became the key – and this can be seen in the legacy of buildings that this era has produced: minimalist structures, often temporary and built of cheap, mass-produced materials, unlikely to survive down the centuries for future generations to marvel at.

The second development, a result of increased economic prosperity and stability, was the blurring of the divide between the haves and the have-nots, and the rise of the affluent middle-classes. This, along with the booms in immigration both after the Second World War and with the opening up of Europe at the end of the Twentieth century, led to an explosion in the demand for affordable housing and – as a result – land became a valuable commodity.

This shift of focus to the needs of the populace, coupled with the need for more and more land to build on, is perhaps a greater threat to face our legacy of historical buildings than the gunpowder and cannons of old. Throughout the last century, despite the work of bodies such as English Heritage and the National Trust in preserving much of our heritage for the public, many beautiful and unique buildings and their lands have been sold off. These valuable national heirlooms have been divided up, demolished and obliterated, to be replaced with uniform, utilitarian housing estates and commercial industrial sites. Unlike the Romans, the Elizabethans and the Victorians, our modern architects rarely seek to continue the cycle of history. Their concern is to build extensively, efficiently and cheaply – as the vast, faceless, prefabricated silos of our modern commercial parks testify.

Where we do seek to be innovative in our buildings, often there is an element of form over content, and a sense of building for the moment rather than for the future. Sir Norman Foster’s impressive glass structures for example, whilst visually stunning and highly innovative, are unlikely to remain intact for centuries to come.

Given this fact, and given that the demand for land for new housing is continuing to grow, it is perhaps a small comfort that we do at least have the means to capture a sense of what we are losing and have already lost. With the advent of photography, of film and more recently the Internet, we have the means to preserve the images of the constructions that have vanished forever, to document for future generations the legacy of our ancestors which we have sold off in the name of progress.

This account seeks to preserve what remains of one of those lost heirlooms, a place variously known as Weddington Hall or Weddington Castle. Evolving from a Royal Hunting Lodge in the ancient village of Weddington to become an extensive fortified Hall set amidst beautifully landscaped gardens, this centuries-old building was demolished in the 1920s to make way for a housing estate. This website cannot serve, therefore, as a guide to your knowledge as you walk through the wooden floored library of the Hall, or ascend the imposing staircase of fine old oak that once greeted visitors, or wander around the picturesque boating lake that graced the Hall’s grounds. It does, however, seek to bring together what remains of this once-splendid building.

Of course, such remains - a handful of black and white photographs, the occasional record in local journals - can never replace the actual physical presence of this lost building; cannot evoke the atmosphere and sense of continuity that one feels when walking on ancient flagstones where kings and queens have walked centuries before. But they can at least serve as a reminder that for all our wealth of history that has survived down the years, there is a sub-strata of history that did not survive. The suburban estates and grey factories of today are built upon the solid foundations and extravagant gardens of once-great manors that now only exist – ghostlike – in faded photographs and historical archives.

When walking around such places, places which have survived and persisted through generation after generation of Britons, it is easy to feel that these solid rock-hewn castles and towering cathedrals are impregnable; that they will simply always be there as a constant national bequest for future generations to inherit.

But history does not stand still, and our ancient fortresses – built to withstand the enemies of their day – are not always proof against the inevitable march of progress. The occupying Romans desecrated centuries-old Druidic temples, Cromwell destroyed castles across the land upon gaining power and Henry VIII obliterated a wealth of ancient abbeys and monasteries. Of course, such destruction has always been cyclical, part of our historical evolution, and for every desecrated temple we have, in the fullness of time, gained a Roman villa. For every devastated castle a magnificent country manor has been constructed.

History, and the buildings which remain as its legacy, is always developing, always evolving. However, in more modern times – from the industrialisation of the Victorian era through to the consumerism of the late twentieth and early twenty-first centuries – a new type of evolution has developed: one which uses up our heritage as a resource, without necessarily replacing it.

As the United Kingdom gained in prosperity at the turn of the Nineteenth century, two key social and political developments occurred. Firstly the country moved from a hierarchical structure, based upon a wide divide between the ruling classes and the masses, to become a capitalist system, based upon the forces of trade and economics. Economy became the key – and this can be seen in the legacy of buildings that this era has produced: minimalist structures, often temporary and built of cheap, mass-produced materials, unlikely to survive down the centuries for future generations to marvel at.

The second development, a result of increased economic prosperity and stability, was the blurring of the divide between the haves and the have-nots, and the rise of the affluent middle-classes. This, along with the booms in immigration both after the Second World War and with the opening up of Europe at the end of the Twentieth century, led to an explosion in the demand for affordable housing and – as a result – land became a valuable commodity.

This shift of focus to the needs of the populace, coupled with the need for more and more land to build on, is perhaps a greater threat to face our legacy of historical buildings than the gunpowder and cannons of old. Throughout the last century, despite the work of bodies such as English Heritage and the National Trust in preserving much of our heritage for the public, many beautiful and unique buildings and their lands have been sold off. These valuable national heirlooms have been divided up, demolished and obliterated, to be replaced with uniform, utilitarian housing estates and commercial industrial sites. Unlike the Romans, the Elizabethans and the Victorians, our modern architects rarely seek to continue the cycle of history. Their concern is to build extensively, efficiently and cheaply – as the vast, faceless, prefabricated silos of our modern commercial parks testify.

Where we do seek to be innovative in our buildings, often there is an element of form over content, and a sense of building for the moment rather than for the future. Sir Norman Foster’s impressive glass structures for example, whilst visually stunning and highly innovative, are unlikely to remain intact for centuries to come.

Given this fact, and given that the demand for land for new housing is continuing to grow, it is perhaps a small comfort that we do at least have the means to capture a sense of what we are losing and have already lost. With the advent of photography, of film and more recently the Internet, we have the means to preserve the images of the constructions that have vanished forever, to document for future generations the legacy of our ancestors which we have sold off in the name of progress.

This account seeks to preserve what remains of one of those lost heirlooms, a place variously known as Weddington Hall or Weddington Castle. Evolving from a Royal Hunting Lodge in the ancient village of Weddington to become an extensive fortified Hall set amidst beautifully landscaped gardens, this centuries-old building was demolished in the 1920s to make way for a housing estate. This website cannot serve, therefore, as a guide to your knowledge as you walk through the wooden floored library of the Hall, or ascend the imposing staircase of fine old oak that once greeted visitors, or wander around the picturesque boating lake that graced the Hall’s grounds. It does, however, seek to bring together what remains of this once-splendid building.

Of course, such remains - a handful of black and white photographs, the occasional record in local journals - can never replace the actual physical presence of this lost building; cannot evoke the atmosphere and sense of continuity that one feels when walking on ancient flagstones where kings and queens have walked centuries before. But they can at least serve as a reminder that for all our wealth of history that has survived down the years, there is a sub-strata of history that did not survive. The suburban estates and grey factories of today are built upon the solid foundations and extravagant gardens of once-great manors that now only exist – ghostlike – in faded photographs and historical archives.

New Mexico

New Mexico

Amarillo

Amarillo

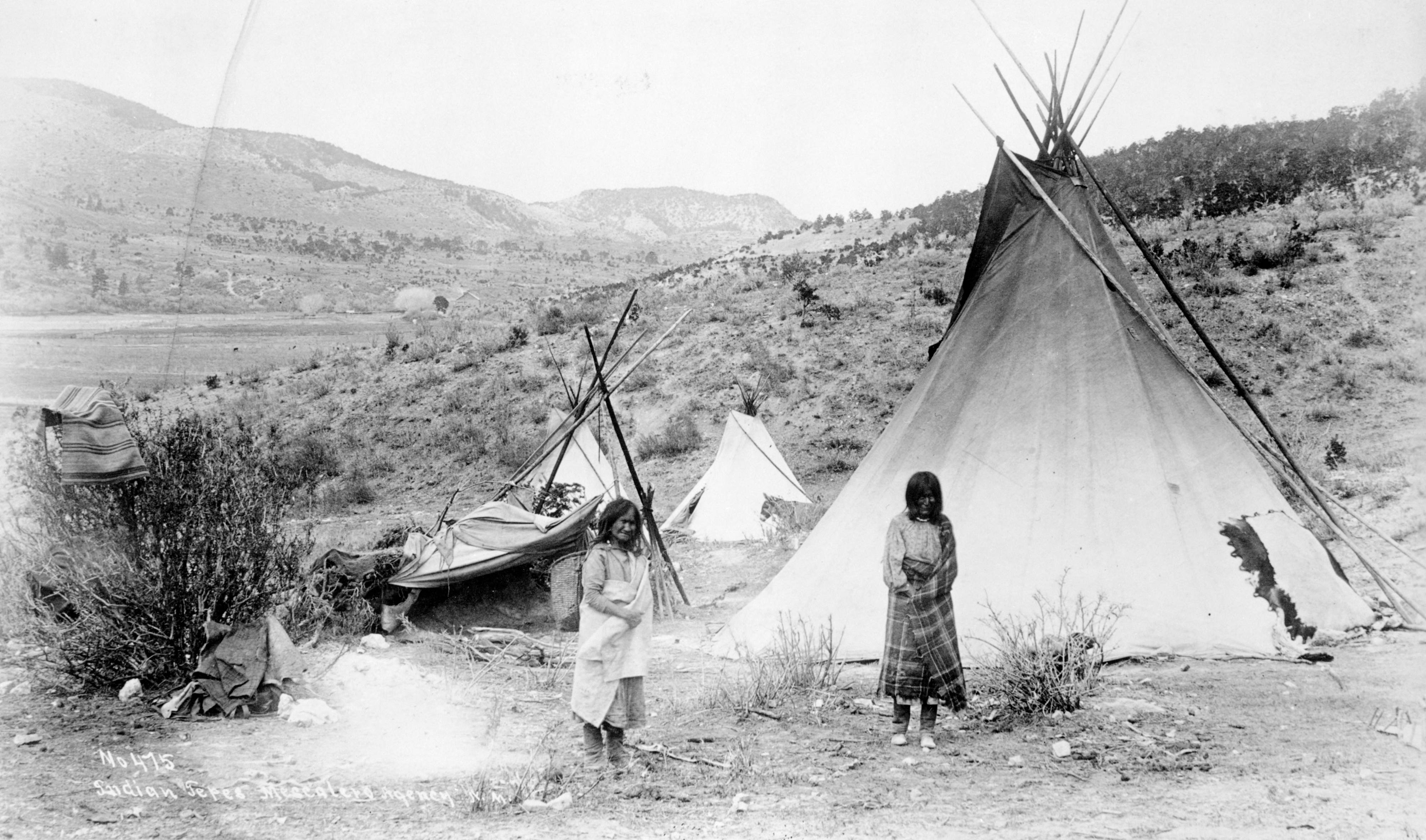

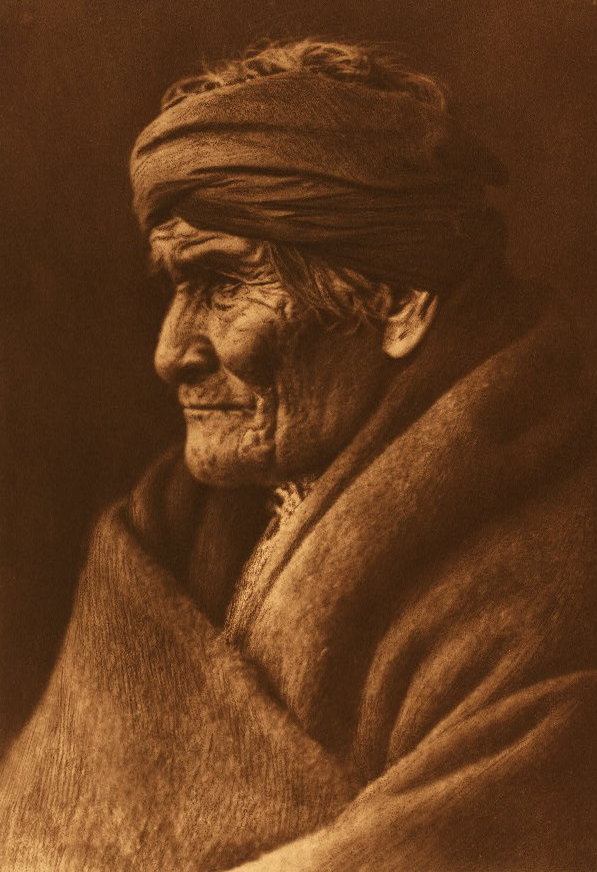

,_called_Dutchy_Chiricahua_scout_(F19052_DPLW).jpg)

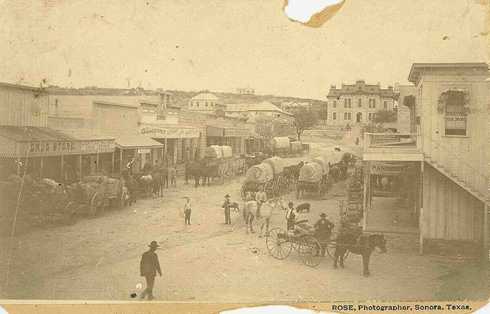

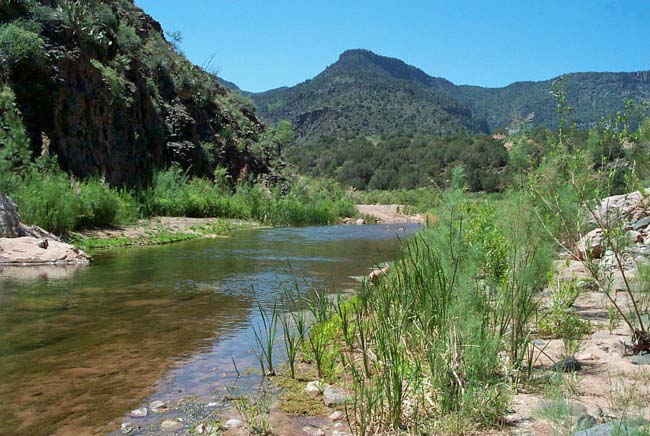

The Cooke's Springs Station of the Butterfield Overland Mail was located near Cooke's Springs from 1858 to 1861.

The Cooke's Springs Station of the Butterfield Overland Mail was located near Cooke's Springs from 1858 to 1861.

Between 1848 and 1861 the pass was a dangerous place for travelers who were often ambushed

Between 1848 and 1861 the pass was a dangerous place for travelers who were often ambushed

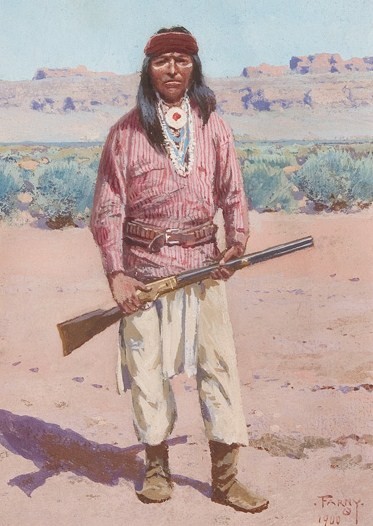

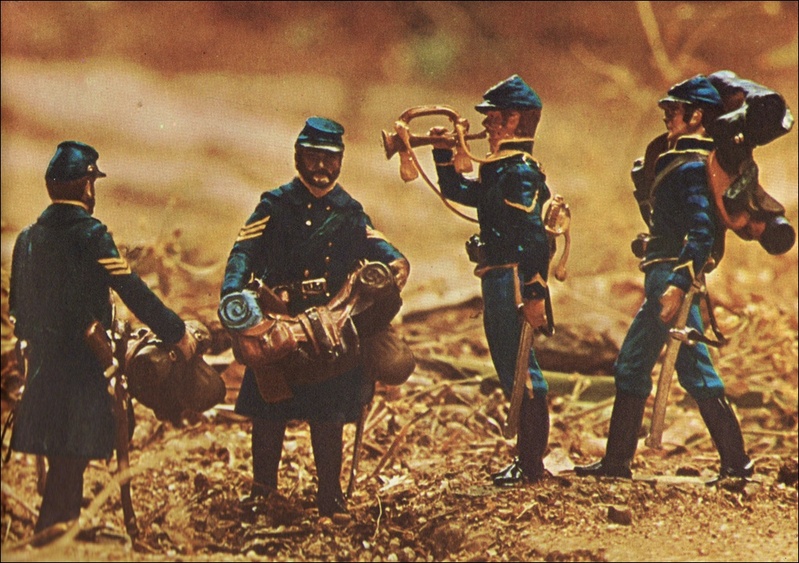

outposts. On campaign the men continued to wear the civil war uniforms that were still in plentiful supply, whilst the new uniform was kept for dress occassions. These are our M1872 Mounted trousers with top opening pockets & re-inforced seat, this pair has Sergeants 1,1/2" yellw wool chevron stripe on the outside leg,

outposts. On campaign the men continued to wear the civil war uniforms that were still in plentiful supply, whilst the new uniform was kept for dress occassions. These are our M1872 Mounted trousers with top opening pockets & re-inforced seat, this pair has Sergeants 1,1/2" yellw wool chevron stripe on the outside leg,  1884 Pattern trousers

1884 Pattern trousers 1884 Infantry pattern trousers

1884 Infantry pattern trousers

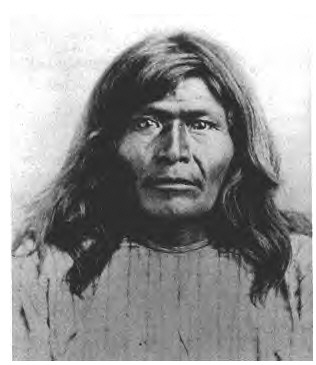

who directed Lieutenant George Nicholas Bascom

who directed Lieutenant George Nicholas Bascom  and a large group of infantry to attempt to recover the boy. Bascom and his men were unable to locate the boy or the tribe. Bascom determined that the raid was done by Chiricahua Apache Indians. Morrison ordered Bascom to use whatever means necessary to punish the kidnappers and recapture the boy.

and a large group of infantry to attempt to recover the boy. Bascom and his men were unable to locate the boy or the tribe. Bascom determined that the raid was done by Chiricahua Apache Indians. Morrison ordered Bascom to use whatever means necessary to punish the kidnappers and recapture the boy. to meet with him. Suspicious of Bascom's plans, Cochise brought with him his brother Coyuntwa, two nephews, his wife, and his two children.At the meeting, Cochise claimed he knew nothing of the affair. Doubting the Indian's honesty, Bascom attempted to imprison him and his family in a tent to be held hostage, but Cochise was able to escape with only a leg wound. Bascom met Cochise at Apache Pass

to meet with him. Suspicious of Bascom's plans, Cochise brought with him his brother Coyuntwa, two nephews, his wife, and his two children.At the meeting, Cochise claimed he knew nothing of the affair. Doubting the Indian's honesty, Bascom attempted to imprison him and his family in a tent to be held hostage, but Cochise was able to escape with only a leg wound. Bascom met Cochise at Apache Pass and captured him. Cochise escaped and Bascom captured five members of Cochise's family in retaliation, prompting Cochise to lay ambushes and capture four Americans whom he offered to trade for his family members.

and captured him. Cochise escaped and Bascom captured five members of Cochise's family in retaliation, prompting Cochise to lay ambushes and capture four Americans whom he offered to trade for his family members.

of Tír Eoghain, Hugh Roe O'Donnell

of Tír Eoghain, Hugh Roe O'Donnell  of Tír Chonaill and their allies, against English rule in Ireland. The war was fought in all parts of the country, but mainly in the northern province of Ulster. It ended in defeat for the Irish chieftains, which led to their exile in the Flight of the Earls

of Tír Chonaill and their allies, against English rule in Ireland. The war was fought in all parts of the country, but mainly in the northern province of Ulster. It ended in defeat for the Irish chieftains, which led to their exile in the Flight of the Earls

Tyrone, Fermanagh, Cavan, Coleraine and Armagh. Most of the counties Antrim

Tyrone, Fermanagh, Cavan, Coleraine and Armagh. Most of the counties Antrim and Down were privately colonised

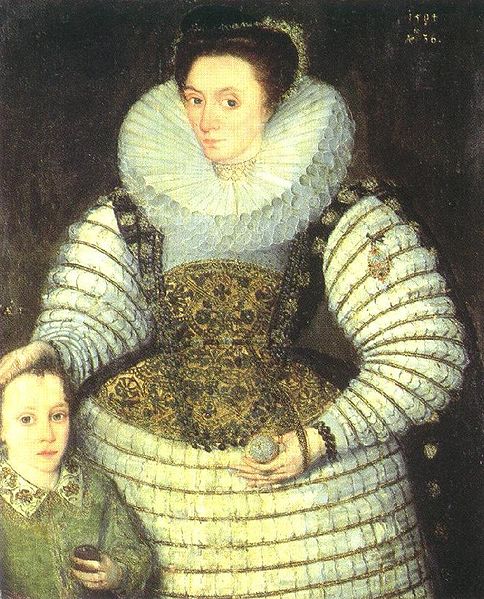

and Down were privately colonised and educated at Trinity College, Cambridge.His father died in 1576. The new Earl of Essex became a ward of Lord Burghley.

and educated at Trinity College, Cambridge.His father died in 1576. The new Earl of Essex became a ward of Lord Burghley. On 21 September 1578 his mother married Robert Dudley,

On 21 September 1578 his mother married Robert Dudley,  Earl of Leicester, Elizabeth I's long-standing favourite and Robert Devereux's godfather.

Earl of Leicester, Elizabeth I's long-standing favourite and Robert Devereux's godfather.

daughter of Sir Francis Walsingham

daughter of Sir Francis Walsingham and widow of Sir Philip Sidney,

and widow of Sir Philip Sidney, by whom he was to have several children, three of whom survived into adulthood. Sidney, Leicester's nephew, died at the Battle of Zutphen in which Essex also distinguished himsel

by whom he was to have several children, three of whom survived into adulthood. Sidney, Leicester's nephew, died at the Battle of Zutphen in which Essex also distinguished himsel on 22 September 1586, near Zutphen

on 22 September 1586, near Zutphen (Warnsveld), the Netherlands.

(Warnsveld), the Netherlands. It was fought between forces of the United Provinces of the Netherlands, aided by the English, against the Spanish,

It was fought between forces of the United Provinces of the Netherlands, aided by the English, against the Spanish,  who sought to regain the northern Netherlands.

who sought to regain the northern Netherlands.

Peregrine Bertie,

Peregrine Bertie, George Whetstone,

George Whetstone, Henry Unton,

Henry Unton,  and Robert Sidney,

and Robert Sidney, whose brother, Philip, was mortally wounded during the battle and died in Arnhem at the age of 31. A story about Sir Philip Sidney (intended as an illustration of his noble character) is that he gave his water-bottle to another wounded soldier, saying, "Thy need is greater than mine". Dudley knighted Welsh mercenary Roger Williams for his performance during the battle.(above Willie 30mm at Tradition)

whose brother, Philip, was mortally wounded during the battle and died in Arnhem at the age of 31. A story about Sir Philip Sidney (intended as an illustration of his noble character) is that he gave his water-bottle to another wounded soldier, saying, "Thy need is greater than mine". Dudley knighted Welsh mercenary Roger Williams for his performance during the battle.(above Willie 30mm at Tradition) Oxford. He spent most of his life soldiering, mainly on the continent. He was in the Netherlands fighting on behalf of William the Silent,

Oxford. He spent most of his life soldiering, mainly on the continent. He was in the Netherlands fighting on behalf of William the Silent,  Prince of Orange, when the latter was assassinated, and helped capture the assassin, Balthasar Gérard.

Prince of Orange, when the latter was assassinated, and helped capture the assassin, Balthasar Gérard. on July 10, 1584, by shooting him twice with a pistol, and was afterwards tried, convicted, and gruesomely executed.After the reward offered by Philip of spain was published Gérard left for Luxembourg where he learned that Juan de Jáuregui

on July 10, 1584, by shooting him twice with a pistol, and was afterwards tried, convicted, and gruesomely executed.After the reward offered by Philip of spain was published Gérard left for Luxembourg where he learned that Juan de Jáuregui was already preparing to attempt the assassination, but did not succeed.Juan de Jáuregui (1562 – March 18, 1582) was killed trying to assassinate Prince William I of Orange. He was a Biscayan by his birth in Bilbao.

was already preparing to attempt the assassination, but did not succeed.Juan de Jáuregui (1562 – March 18, 1582) was killed trying to assassinate Prince William I of Orange. He was a Biscayan by his birth in Bilbao. for the assassination of William the Silent, prince of Orange, and being himself without courage to undertake the task, De Añastro (with the help of his cashier Antonio de Venero, a 19-year-old also from Bilbao, and the Dominican monk Antonio Timmerman, from Dunkirk) persuaded his poor accounting assistant Jáuregui to attempt the murder for the sum of 2877 crowns.

for the assassination of William the Silent, prince of Orange, and being himself without courage to undertake the task, De Añastro (with the help of his cashier Antonio de Venero, a 19-year-old also from Bilbao, and the Dominican monk Antonio Timmerman, from Dunkirk) persuaded his poor accounting assistant Jáuregui to attempt the murder for the sum of 2877 crowns.

, and the Christ of Burgos. There also was a letter appealing to the goodwill of the Antwerpers. In March 1584 he went to Trier,

, and the Christ of Burgos. There also was a letter appealing to the goodwill of the Antwerpers. In March 1584 he went to Trier,

In Tournai, after holding counsel with aFranciscan, Father Gery, Gérard wrote a letter, a copy of which was deposited with the guardian of the convent, and the original presented personally to the Prince of Parma. In the letter Gérard wrote, in part, "The vassal ought always to prefer justice and the will of the king to his own life

In Tournai, after holding counsel with aFranciscan, Father Gery, Gérard wrote a letter, a copy of which was deposited with the guardian of the convent, and the original presented personally to the Prince of Parma. In the letter Gérard wrote, in part, "The vassal ought always to prefer justice and the will of the king to his own life A halberdier asked him why he was waiting there. He excused himself by saying that in his shabby clothing and without new shoes he was unfit to join the congregation in the church opposite. The halberdier unsuspectingly arranged a gift of 50 crowns for Gérard, who, the following morning purchased a pair of pistols from a soldier, haggling the price for a long time because the soldier couldn't supply the particular chopped bullets or slugs he wanted.

A halberdier asked him why he was waiting there. He excused himself by saying that in his shabby clothing and without new shoes he was unfit to join the congregation in the church opposite. The halberdier unsuspectingly arranged a gift of 50 crowns for Gérard, who, the following morning purchased a pair of pistols from a soldier, haggling the price for a long time because the soldier couldn't supply the particular chopped bullets or slugs he wanted. Williams was recognised as an expert on military matters by his contemporaries, and wrote A brief discourse of war (1590).

Williams was recognised as an expert on military matters by his contemporaries, and wrote A brief discourse of war (1590).

,Gebhard Truchsess von Waldburg, and fought with the Dutch soldier of fortune, Martin Schenck von Nydeggen in Westphalia.

,Gebhard Truchsess von Waldburg, and fought with the Dutch soldier of fortune, Martin Schenck von Nydeggen in Westphalia.

On one occasion during a heated Privy Council debate on the problems in Ireland, the Queen reportedly cuffed an insolent Essex round the ear, prompting him to half draw his sword on her.

On one occasion during a heated Privy Council debate on the problems in Ireland, the Queen reportedly cuffed an insolent Essex round the ear, prompting him to half draw his sword on her. which sailed to Spain in an unsuccessful attempt to press home the English advantage following the defeat of the Spanish Armada; the Queen had ordered him not to take part in the expedition, but he only returned upon the failure to take Lisbon. In 1591, he was given command of a force sent to the assistance of King Henry IV of France.

which sailed to Spain in an unsuccessful attempt to press home the English advantage following the defeat of the Spanish Armada; the Queen had ordered him not to take part in the expedition, but he only returned upon the failure to take Lisbon. In 1591, he was given command of a force sent to the assistance of King Henry IV of France. In 1596, he distinguished himself by the capture of Cadiz.

In 1596, he distinguished himself by the capture of Cadiz. During the Islands Voyage expedition to the Azores in 1597

During the Islands Voyage expedition to the Azores in 1597 , with Walter Raleigh as his second in command, he defied the Queen's orders, pursuing the treasure fleet without first defeating the Spanish battle fleet

, with Walter Raleigh as his second in command, he defied the Queen's orders, pursuing the treasure fleet without first defeating the Spanish battle fleet

and so the voyage proved a failure. It was thus the last major expedition sent to sea by Elizabeth I and contributed to Essex's decline in favour with Elizabeth.Essex's greatest failure was as Lord Lieutenant of Ireland, a post which he talked himself into in 1599. The Nine Years War (1595–1603) was in its middle stages, and no English commander had been successful. More military force was required to defeat the Irish chieftains, led by Hugh O'Neill, the Earl of Tyrone, and supplied from Spain and Scotland.

and so the voyage proved a failure. It was thus the last major expedition sent to sea by Elizabeth I and contributed to Essex's decline in favour with Elizabeth.Essex's greatest failure was as Lord Lieutenant of Ireland, a post which he talked himself into in 1599. The Nine Years War (1595–1603) was in its middle stages, and no English commander had been successful. More military force was required to defeat the Irish chieftains, led by Hugh O'Neill, the Earl of Tyrone, and supplied from Spain and Scotland.

before she was properly wigged or gowned. On that day, the Privy Council met three times, and it seemed his disobedience might go unpunished, although the Queen did confine him to his rooms with the comment that "an unruly beast must be stopped of his provender."

before she was properly wigged or gowned. On that day, the Privy Council met three times, and it seemed his disobedience might go unpunished, although the Queen did confine him to his rooms with the comment that "an unruly beast must be stopped of his provender." Lord Mountjoy,

Lord Mountjoy, although any plans he may have had at that time to help the Scots king capture the English throne came to nothing. In October, Mountjoy was appointed to replace him in Ireland, and matters seemed to look up for the Earl. In November, the queen was reported to have said that the truce with O'Neill was "so seasonably made... as great good... has grown by it." Others in the Council were willing to justify Essex's return to Ireland, on the grounds of the urgent necessity of a briefing by the commander-in-chief.Essex appeared before the full Council on 29 September, when he was compelled to stand before the Council during a five hour interrogation. The Council — his uncle William Knollys included — took a quarter of an hour to compile a report, which declared that his truce with O'Neill was indefensible and his flight from Ireland tantamount to a desertion of duty. He was committed to the custody of Sir Richard Berkeley in

although any plans he may have had at that time to help the Scots king capture the English throne came to nothing. In October, Mountjoy was appointed to replace him in Ireland, and matters seemed to look up for the Earl. In November, the queen was reported to have said that the truce with O'Neill was "so seasonably made... as great good... has grown by it." Others in the Council were willing to justify Essex's return to Ireland, on the grounds of the urgent necessity of a briefing by the commander-in-chief.Essex appeared before the full Council on 29 September, when he was compelled to stand before the Council during a five hour interrogation. The Council — his uncle William Knollys included — took a quarter of an hour to compile a report, which declared that his truce with O'Neill was indefensible and his flight from Ireland tantamount to a desertion of duty. He was committed to the custody of Sir Richard Berkeley in his own York House on 1 October,

his own York House on 1 October,

and to Sir Balthazar Gerbier,

and to Sir Balthazar Gerbier, diplomat and sometime painter; though after the Duke's assassination in 1628, the Duchess tried to expel him, it was in Gerbier's lodgings that Peter Paul Rubens soujourned during his visit to London this following year. An inventory of the contents of York House drawn up in 1635 is mined by scholars both for the light it sheds on one of the handful of great art collections formed in the circle of Charles I, and the furnishings of a fashionable Early Stuart nobleman's residence. In the 'Great Chamber' twenty-two paintings were displayed with fifty-nine pieces of Roman sculpture, many of which were heads. In the 'Gallery' were a further thirty-one further heads and statues. Apparently the only modern sculpture at York House was

diplomat and sometime painter; though after the Duke's assassination in 1628, the Duchess tried to expel him, it was in Gerbier's lodgings that Peter Paul Rubens soujourned during his visit to London this following year. An inventory of the contents of York House drawn up in 1635 is mined by scholars both for the light it sheds on one of the handful of great art collections formed in the circle of Charles I, and the furnishings of a fashionable Early Stuart nobleman's residence. In the 'Great Chamber' twenty-two paintings were displayed with fifty-nine pieces of Roman sculpture, many of which were heads. In the 'Gallery' were a further thirty-one further heads and statues. Apparently the only modern sculpture at York House was Giambologna's SSamson and a Philistine, a royal gift from Philip IV of Spain to Charles I, who passed it to his favourite, Buckingham.

Giambologna's SSamson and a Philistine, a royal gift from Philip IV of Spain to Charles I, who passed it to his favourite, Buckingham.

of the London headquarters of the Knights Templar. It was re-named Essex House after being inherited by Robert Devereux, 2nd Earl of Essex in 1588. The house was substantial. In 1590, it was recorded as having 42 bedrooms, plus a picture gallery, kitchens, outhouses, a banqueting suite and a chapel.

of the London headquarters of the Knights Templar. It was re-named Essex House after being inherited by Robert Devereux, 2nd Earl of Essex in 1588. The house was substantial. In 1590, it was recorded as having 42 bedrooms, plus a picture gallery, kitchens, outhouses, a banqueting suite and a chapel. Seymour, 1st Marquess of Hertford. After the English Civil War, the family lost ownership as a result of their debts. Following the Restoration and the death of William Seymour, Sir Orlando Bridgeman

Seymour, 1st Marquess of Hertford. After the English Civil War, the family lost ownership as a result of their debts. Following the Restoration and the death of William Seymour, Sir Orlando Bridgeman  lived in the house for a time. When the Duchess of Somerset died in 1674, she left the house to her granddaughter, whose husband, Sir Thomas Thynne, sold it, along with the adjoining lands and properties.

lived in the house for a time. When the Duchess of Somerset died in 1674, she left the house to her granddaughter, whose husband, Sir Thomas Thynne, sold it, along with the adjoining lands and properties.

are still on the site, now called Essex Hall. Their building footprint is believed to include the Tudor chapel of Essex House On the morning of 8 February, he marched out of Essex House with a party of nobles and gentlemen

are still on the site, now called Essex Hall. Their building footprint is believed to include the Tudor chapel of Essex House On the morning of 8 February, he marched out of Essex House with a party of nobles and gentlemen

was apprehended as he kept watch on the door to the Queen's chambers. His plan had been to confine her until she signed a warrant for the release of Essex. Capt. Lee, who had served in Ireland with the Earl, and who acted as go-between with the Ulster rebels, was tried and put to death the next day.

was apprehended as he kept watch on the door to the Queen's chambers. His plan had been to confine her until she signed a warrant for the release of Essex. Capt. Lee, who had served in Ireland with the Earl, and who acted as go-between with the Ulster rebels, was tried and put to death the next day. . However, after the Queen's death, King James I reinstated the earldom in favour of the disinherited son, Robert Devereux, 3rd Earl of Essex

. However, after the Queen's death, King James I reinstated the earldom in favour of the disinherited son, Robert Devereux, 3rd Earl of Essex