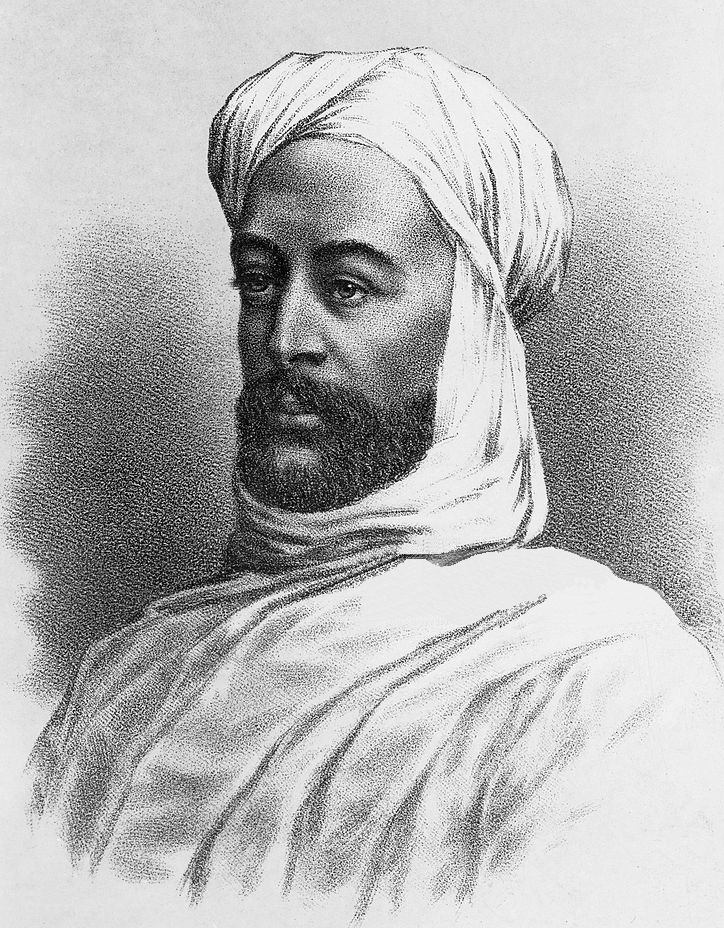

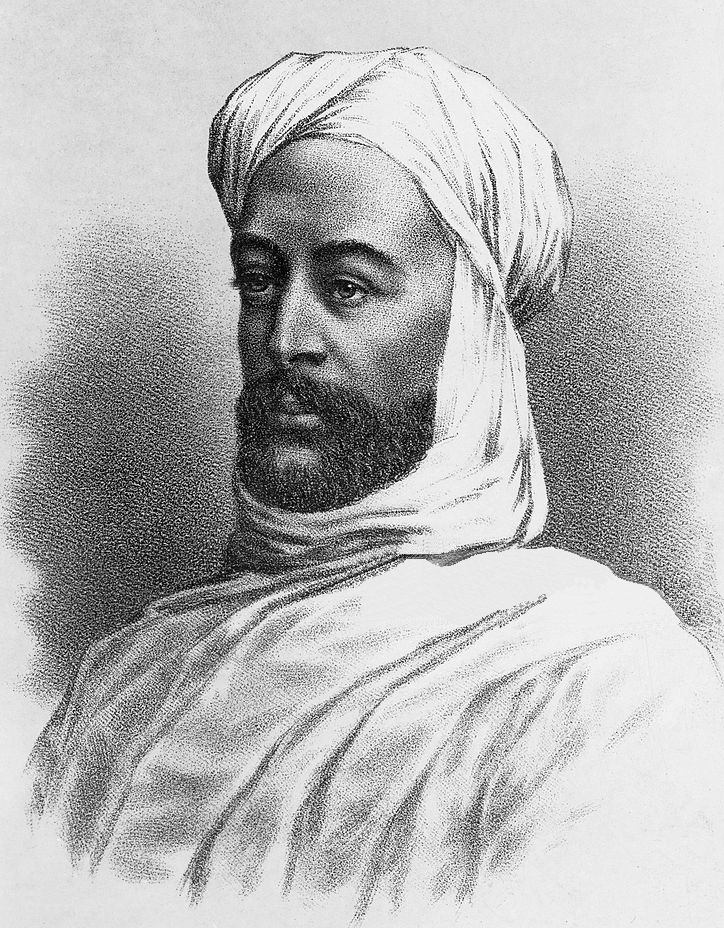

Muhammad Ahmad bin Abd Allah in arabic محمد أحمد المهدي) (August 12, 1845 – June 22, 1885) was a religious leader of the Samaniyya order in Sudan who, on June 29, 1881, proclaimed himself as the Mahdi or messianic redeemer of the Islamic faith. His proclamation came during a period of widespread resentment

among the Sudanese population of the oppressive policies of the Turco-Egyptian rulers, and capitalized on the messianic beliefs popular among the various Sudanese

religious sects of the time. More broadly, the Mahdiyya, as Muhammad Ahmad's movement was called, was influenced by earlier Mahdist movements in West Africa, as well as Wahabism

and other puritanical forms of Islamic revivalism that developed in reaction to the growing military and economic dominance of the European powers throughout the 19th century.

From his announcement of the Mahdiyya in June 1881 until the fall of Khartoum in January 1885, Muhammad Ahmad led a successful military campaign against the Turco-Egyptian government of the Sudan (known as the Turkiyah). During this period, many of the theological and political doctrines of

the Mahdiyya were established and promulgated among the growing ranks of the Mahdi's supporters. After Muhammad Ahmad's unexpected death on 22 June 1885, a mere six months after the conquest of

Khartoum, his chief deputy, Abdallahi ibn Muhammad took over the administration of the nascent Mahdist state.

Muhammad Ahmad was born on 12 August 1845 at Port Sudan

in Northern Sudan to a family of descendants of the Prophet Muhammad through the line of his grandson Hassan. As a child, the family moved to the town of Karari, north of Omdurman,

where Muhammad Ahmad's father, Abdullah, could find a supply of timber for his boat-building business.

While his siblings joined his father's trade, Muhammad Ahmad showed a proclivity for religious

e studied first under Sheikh al-Amin al-Suwaylih in the Gezira region around Khartoum, and subsequently under Sheikh Muhammad al-Dikayr 'Abdallah Khujali near the town of Berber in North Sudan. Determined to live a life of asceticism, mysticism and worship, i

he sought out Sheikh Muhammad Sharif Nur al-Dai'm, the grandson of the founder of the Samaniyya Sufi sect in Sudan.

Muhammad Ahmad stayed with Sheikh Muhammad Sharif for seven years, during which time he was recognized for his piety and as

nd of this period, he was awarded the title of Sheikh himself, and began to travel around the country on religious missions. He was permitted to give tariqa and Uhūd to new followers.

In 1870, his family moved again in search for timber, this time to Aba Island on the White Nile south of Khartoum. On Aba Island, Muhammad Ahmad built a mosque and started to teach the Qur'an. He soon

gained a notable reputation among the local population as an excellent speaker and mystic.

The broad thrust of his teaching followed that of other reformers, his Islam was one devoted to the words of Muhammad and based on a return to the virtues of strict devotion, prayer

mplicity as laid down in the Qur'an. Any deviation from the Qur'an was therefore heresy.

In 1872, Muhammad Ahmad invited Sheikh Sharif to move to al-Aradayb, an area on the White Nile neighboring Aba Island.

Despite initially amicable relations, in 1878 the two religious leaders had a dispute motivated by Sheikh Sharif's resentment of his former student's growing popularity. The dispute led to violence between their followers, and while they temporarily reconciled their differences, the experience revealed to Muhammad Ahmad his mentor's ostensible faults. At a subsequent celebration in honor of the circumcision of Sheikh Sharif's sons, Muhammad Ahmad expressed his disapproval of the dancing and music, which reignited the latent tension between the two men. As a result of this second dispute, Sheikh Sharif expelled his former student from the Samaniyya order, and despite numerous apologies and emotional appeals, refused to forgive and re-admit him.

After recognizing that the split with Sheikh Sharif was irreconcilable, Muhammad Ahmad approached a rival leader of the Samaniyya order named Sheikh al-Qurashi wad al-Zayn.

The elderly sheikh eagerly accepted him and his followers, and under his new master, Muhammad Ahmad resumed his life of piety and religious devotion at Aba Island.

During this period, he also travelled to the province of Kordofan, west of Khartoum, where he visited with the notables of the capital, el-Obeid,

who were enmeshed in a power struggle between two rival claimants to the governorship of the province. While in Kordofan, he also enhanced his reputation by granting baraka to the common people who attended his sermons en masse

On 25 July 1878, Sheikh al-Qurashi died and his followers recognized Muhammad Ahmad as their new leader. Around this time, Muhammad Ahmad first met Abdallahi bin Muhammad al-Ta'aishi, who was to become his chief deputy and successor in the years to come.

On 29 June 1881, Muhammad Ahmad publicly announced his claim to be the Mahdi so as to prepare the way for the second coming of the Prophet Isa (Jesus).

In part, his claim was based on his status as a prominent Sufi sheikh with a large following in the Samaniyya order and among the tribes in the area around Aba Island Yet the idea of the Mahdiyya had been central to the belief of the Samaniyya prior to Muhammad Ahmad's manifestation. The previous Samaniyya leader, Sheikh al-Qurashi Wad al-Z

ad asserted that the long-awaited-for redeemer would come from the Samaniyya line. According to Sheikh al-Qurashi, the Mahdi would make himself known through a number of signs, some established in the early period of Islam and recorded in the Hadith literature, and others having a more distinctly local origin, such as the prediction that the Mahdi would ride the sheikh's pony and erect a dome over his grave after his death.

Drawing from aspects of the Sufi tradition that were intimately familiar to both his followers and his

opponents, Muhammad Ahmad claimed that he had been appointed as the Mahdi by a prophetic assembly or hadra (Arabic: Al-Hadra Al-Nabawiyya, الحضرة النبوية). A hadra, in the Sufi tradition, is a gathering of all

the prophets from the time of Adam to Muhammad, as well as many Sufi holy men who are believed to have reached the highest level of affinity with the divine during their lifetime. The hadra is chaired by the Prophet

Muhammad, known as Sayyid al-Wujud, and at his side are the seven Qutb, the most senior of whom is known as Ghawth az-Zaman. In the belief system of the Mahdiyya, it was this divine assembly that bestowed upon Muhammad Ahmad the title of al-Mahdi.

The hadra was also the source of a number of central beliefs about the Mahdi, including that Muhammad Ahmad was created from the sacred light at the center of the Prophet's heart, that the Mahdiyya was eternal and the basic institution of the universe, and that all living creatures had acknowledged the Mahdi's claim since his birth.

In order to frame the Mahdiyya as a return to the early days of Islam, when the Muslim community, or Ummah, was unified under the guidance of the Prophet Muhammad and his immediate successors, Muhammad Ahmad drew many parallels between his manifestation as the Mahdi and the career of the Prophet.

For example, he referred to himself as the Successor of the Messenger of God (Arabic: Khalifat Rasul Allah, خليفة رسول الله), and named his four closest deputies after the four successors to the Prophet Muhammad. Later, in order to distinguish his followers from adherents of other Sufi sects, he forbid the use of the word darwish (commonly known as "dervish" in English) to describe his followers, replacing it with the title Ansar, the term the Prophet Muhammad used for the people of Medina who welcomed him and his followers after their flight from Mecca.

This revivalist vision of the Mahdi intersected with the popular beliefs and legends of the Mahdi. Many of these beliefs have obscure origins in unsubstantiated Hadith, or are influenced by a convergence of local mythologies, Shi'a concepts, and Sufi traditions. It was believed that the Mahdi would manifest himself at the turn of an Islamic century, that his coming would herald in the end of time, that he would revitalize the faith and restore unity to the Ummah, and that his reign would last for eight years. At the end of his reign, it was believed that he would be defeated in battle with the anti-Christ (al-Dajjal), who would subsequently be vanquished by the return of Jesus (Nabi 'Isa)

Despite his popularity among the clerics of the Samaniyya and other sects, and among the tribes of western Sudan, the Ulema, or Orthodox religious authorities, ridiculed Muhammad Ahmad's claim to be the Mahdi. Among his most prominent critics were the Sudanese Ulema loyal to the Ottoman Sultan and in the employ of the Turco-Egyptian government, such as the Mufti Shakir al-Ghazi, who sat on the Council of Appeal in Khartoum, and the Qadi Ahmad al-Azhari in Kordofan.

These critics were careful not to deny the concept of the Mahdi as such, but rather to discredit Muhammad Ahmad's claim to it. They pointed out that Muhammad Ahmad's manifestation did not conform to the prophecies laid out in the Hadith literature. In particular, they argued that he had been born in Dongola,

that he lacked proof of descent from Fatima, that he did not have the prophesied physical characteristics of the Mahdi, and that his manifestation did not conform with the "time of troubles" "when the land is filed with oppression, tryanny, and enmity."

While his challenge to the legitimacy of Turco-Egyptian rule, and the Sublime Porte by extension, set many of the religious elite against him, some of his radical changes to Islamic doctrine and practice alienated other Muslim scholars, both Sudanese and foreign. In particular, the Mahdi abolished the four Sunni schools of jurisprudence (Arabic: madhahib, مذاهب), rejected all authoritative texts in the history of tafsir or Qur'anic exegesis, changed the Sha'hada, or profession of faith, to include the phrase, "Muhammad al-Mahdi is the Khalifa of the Prophet of God," and revised the five pillars of Islam by replacing the Hajj or pilgrimage to Mecca with the obligation to undertake jihad, and adding a sixth pillar, which was belief in the Mahdiyya.

[1. Infantry Sergeant in Grey Serge

The initial force to operate against the Mahdi garrisoned in the Mediterranean (excluding the Naval Brigade) were supplied with grey uniforms. These uniforms were first sent to Egypt in September 1882 after favourable reports of Indian khaki in the late war with the Egyptians. Helmet and 74 valise equipment are stained off-white, mess tin cover and expense pouch (not always worn) are black. Only the greatcoat was carried, not the actual valise. The rifle is the .45in Martini-Henry.

2. English Khaki

Due to the lack of obtaining a satisfactory dye in England khaki only began to replace the grey uniforms in the Sudan in 1885. Not all regiments received it, and only a portion of some. The painting of the battle of Tofrek by C E Fripp shows the Berkshires in action in both uniforms.

3. Royal Marine

Shown here wearing grey but with white pipe clayed helmet, pouches and belts, rather than the more usual stained finish, as observed by Count Gleichen of the Camel Corp.

4. The King’s Royal Rifle Corp.

The KRRC sported their traditional black pouches, belts and buttons. Neck curtains for protection against the sun were not supplied to the army and it was left up to the individual to procure a towel or similar to attach to, or wear under, the helmet. These curtains are nearly always depicted as white.

5. York & Lancaster Regiment

A battalion of this regiment together with others (Royal Irish and East Surrey) arrived from India wearing Indian khaki drill uniforms. It fought with fairly outdated equipment, cartridge pouch and belt from 1854 and 1857 expense pouch. The greatcoat had to be carried over the shoulder. According to Bennet Burleigh of the Telegraph all troops passing through Suakin were issued with Oliver pattern water bottles as shown here.

6. Yorkshire Regiment

The battle of Ginniss (30th December 1885) was the last occasion on which the British army fought in red. At this battle, as well as a couple of others eg. Kirbekan, red was ordered ‘to look more formidable to the Dervishes’. Some units probably remained in their khaki trousers and puttees. Regimental facings on the red frocks were changed in 1881 to white for English and Welsh, yellow for Scottish, green for Irish and blue for royal regiments. This figure has the larger 1882 pattern pouches which have been pipe clayed for the occasion.

7. Gordon Highlanders

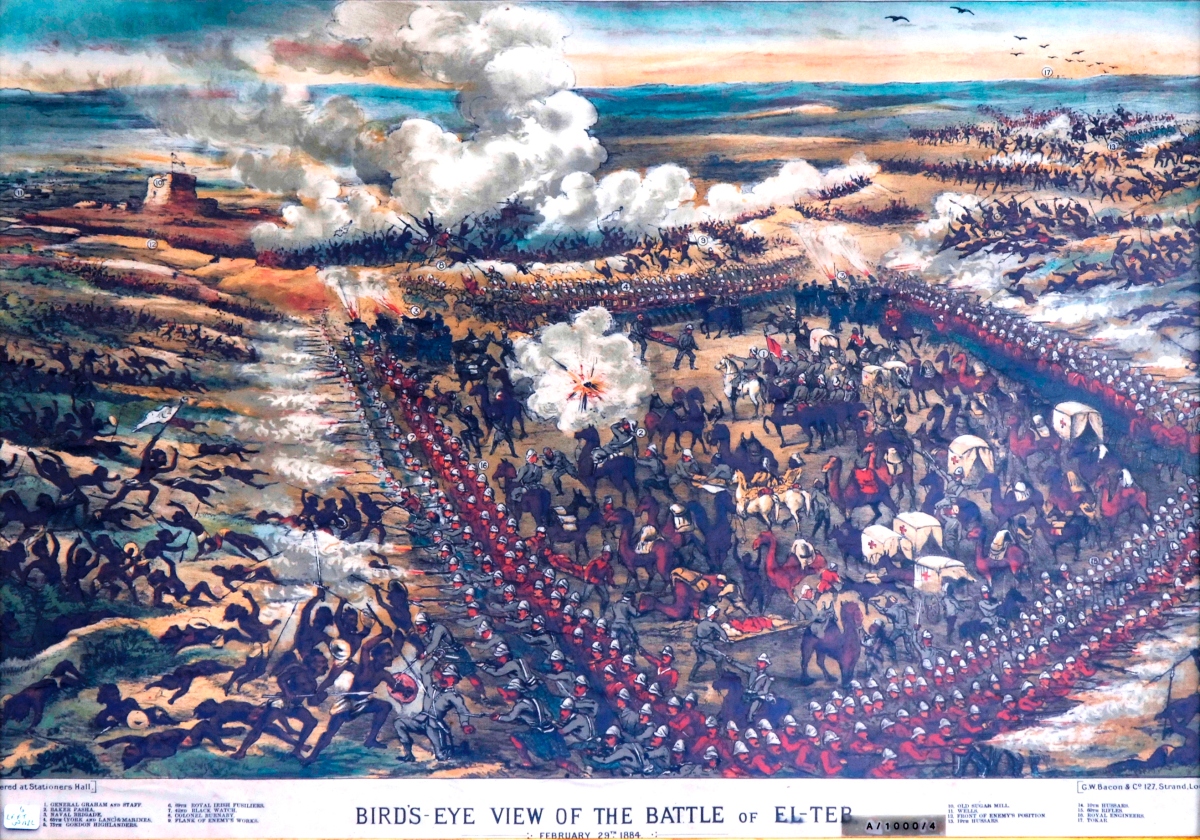

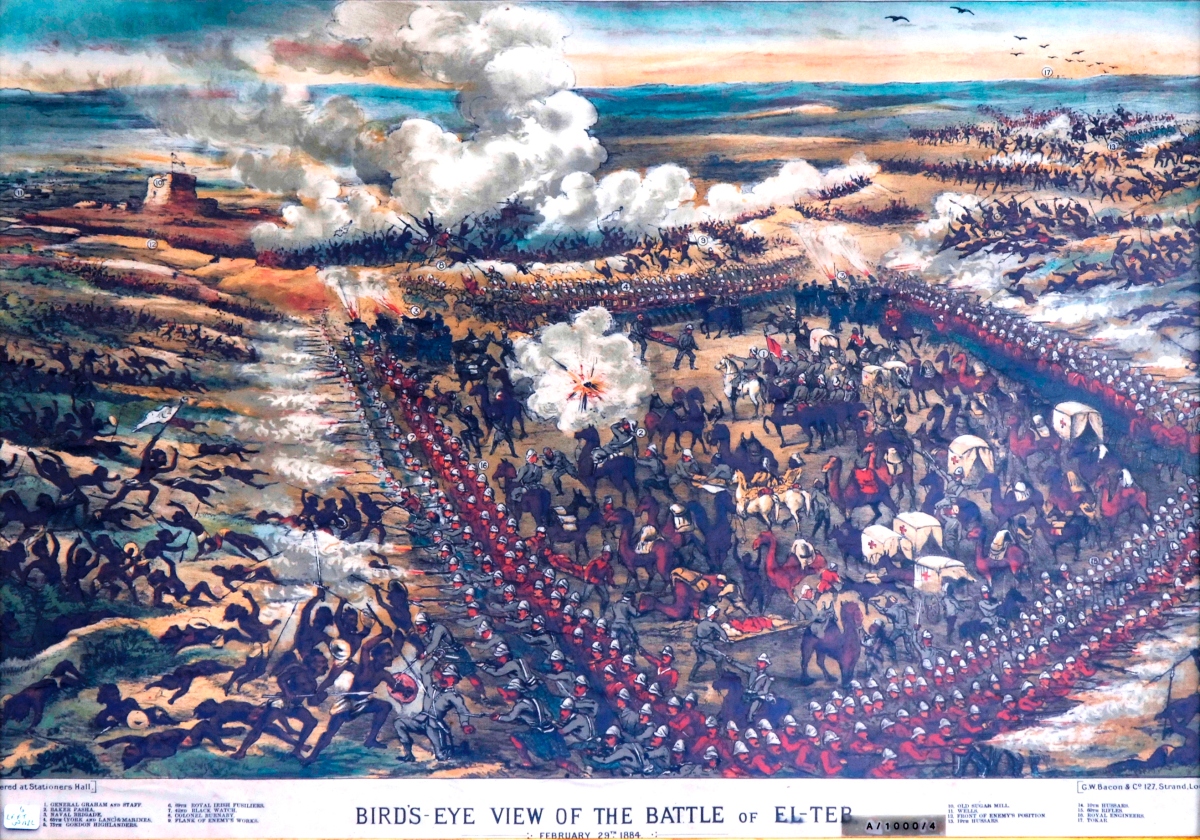

This is the uniform worn by the highlanders at the battles of El Teb, 29th February 1884 and Tamai, 13th March 1884.

8. The Black Watch

Similar to the above apart from the tartan, sporran and the addition of the red hackle. Melton Prior, the war artist, shows them with the 1874 valise as in fig.1, but with a Glengarry under the straps of the greatcoat. Other units do not seem to have carried their forage caps.

9. Cameron Highlanders

At the battle of Ginniss this unit was ordered into red from it’s khaki.

10. 15th Bengal Infantry (Ludhiana Sikhs)

Sikhs fought in their khaki drill with brown leather equipment and puttees. Indian infantry were armed with Snider rifle.

11. 28th Bombay Infantry

Again clothed in their Indian khaki and brown equipment but with canvas leggings.

12. New South Wales Contingent

This was the first war in which Australians were involved. They arrived wearing their home service dress, ie. red frock and white helmet, they soon received a shipment of English khaki, 1882 valise equipment and leggings although the latter were not popular and trousers were often left loose. Australia supplied one battalion of infantry (volunteers) and a battery of artillery.

13. Grenadier Guards

On the 12th March 1885 the Guards Brigade consisting of 1st Bn Coldstream Guards, 2nd Bn Scots Guards and 3rd Bn Grenadier Guards arrived in Suakin with two khaki suits per man. They wore 1882 valise equipment and also, unusually their regimental badges on the front of their puggarees.

14. South Staffordshire Regiment

14. South Staffordshire Regiment

This regiment and the Black Watch were ordered to wear red to storm the ridge at the battle of Kirbekan, 10th February 1885.

15. The Naval Brigade

The Navel brigade manned the Gardiner and Gatling machine guns. Pistol and cutlass were the personal armourment of the crews, who were in turn protected by a detachment of Martini Henry armed sailors with the equipment as pictured here. Major Giles’s picture of Tamai shows them in this uniform with white covered caps, a drawing by A Forester shows them wearing sennet hats and white trousers as is shown on the 2nd figure, whilst Dickenson has them in helmets, shirts sleeves and white trousers.

16. Royal Artillery

This is their probable uniform at El Teb. A Forester’s drawing of the battle of Ginniss depicts them in what looks to be a mix of home service dark blue trousers and either dark blue or khaki frocks. Puttees are either dark blue or khaki.

17. 19th Hussars

The 19th wore the standard grey serge frocks but with Bedford cord pantaloons and home service boots. After El Teb Burleigh says that the cavalry were ordered to arm themselves with native spears which were found to be far more effective than swords for reaching enemy going prone at the point of impact.

18. 10th Hussars

On the other hand the 10th arrived from India at the beginning of the war in Khaki. Their blue pantaloons had double yellow welts and their uncovered helmets kept their parade spikes. They also kept their Indian pattern water bottles. Officers retained their black leather and gilt cartridge pouch belt and black undress sabertache. The carbines were Martini Henry.

19. 5th Dragoon Guards, Camel Regt.

The Camel Corp of roughly 1,600 men consisted of the Guard’s Camel Regt. (detachments from Grenadier, Coldstream and Scots Guards), Royal Marine Camel Regt., then Heavy Camel Regt. (1st & 2nd Life Guards, Royal Horse Guards, 2nd, 4th & 5th Dragoon Guards, 1st & 2nd Dragoons & 5th & 16th Lancers), the Light Camel Regt. (3rd, 4th, 7th, 11th, 15th, 18th, 20th & 21st Hussars) and the Mounted Infantry Camel Regt. (detachments drawn from most of the infantry regiments out there). The same basic uniform was worn by all with the addition of the battalion number and regimental initials in red on the right sleeve as pictured (a). Armament was the Martini Henry and sword bayonet plus a 50 round bandolier. 6,000 ‘mushroom’ topis (b) were made and sent from India arriving in April 1885. Initially intended for the Camel Corp. they crop up in photos on heads of various units including Australian Artillery and Royal Engineers.

20. Mounted Infantry KRRC

Mounted Infantry were raised from various regiments and mounted on local ponies. Frocks were the same as their parent unit but all wore Bedford cords, blue puttees, 50 round bandolier and carried a Martini Henry and sword bayonet. The pouch and belt on this figure are Rifles issue.

21. 9th Bengal Cavalry

As well as sword and carbine the Bengal Cavalry carried the 9 foot bamboo lance. The colour of the regimental turban which was worn at the battle of Hashin (21st March 1885) is speculative, I can find pictures of all but the 9th!

22. Infantry Officer

Officers tended to wear their own style and cut of uniform and shades of colour also varied. This is the popular Norfolk jacket type with deep pleats at the front which sometimes concealed pockets. He wears boots but puttees were as common and a Sam Browne belt with his own choice of pistol.

23. York & Lancaster Officer

Based on Giles’s officer from his Tamai painting he is from the Indian contingent and, like his men, carries his blanket roll over his shoulder and has a helmet cover. He has blue/black puttees for riding duties.

24. Naval Officer.

He looks a little over dressed for fighting in the Sudan but this was standard for Naval Officers sometimes exchanging puttees for gaiters.

25. 15th Bengal Infantry Officer

Dressed similarly to his men but wearing the Sam Browne belt and armed with a sword and pistol. British officers in Indian regiments wore the European cut of uniform and helmets.

26. Life Guards Officer, Heavy Camel Regt.

This is another version of the Norfolk jacket. Around his puggaree is twisted red cloth which was particular to the Life Guards. Above the puggaree are goggles which were issued to the Camel Corp.After consulting the Ulema, Egyptian authorities attempted to arrest him for spreading false doctrine. A military expedition was sent to reassert the government's authority on Aba Island, but the government's forces were ambushed and nearly annihilated by the Mahdi's followers.

Muhammad Ahmed retaliated by declaring jihad, an act which was highly criticized as unjust by the then scholars of Islam:

I am the Mahdi, the Successor of the Prophet of God. Cease to pay taxes to the infidel Turks and let everyone who finds a Turk kill him, for the Turks are infidels ![[Illustration]](http://www.heritage-history.com/books/langjean/gordon/zpage104.gif)

Unlike other Muslim reformers, the Mahdi did not advocate the application of ijtihad but "claimed to receive direct inspiration from God", so that his own proclamations superseded traditional jurisprudence. This, however, did not usurp the prophet Muhammad's position as seal of the Prophets, because the Prophet was — in some way — the intermediary of his revelations.

Information came from the Apostle of God that the angel of inspiration is with me from God to direct me and He has appointed him. So from this prophetic information I learnt that that with which God inspires me by means of the angel of inspiration, the Apostle of God would do, were he present.

The Mahdi and a party of his followers, the

Ansār "Helpers"

(known in the West as "the Dervishes"), made a long march to Kurdufan. There he gained a large number of recruits, especially from the Baqqara, and notable leaders such as Sheikh Madibbo ibn Ali of Rizeigat and Abdallahi ibn Muhammad of Ta'aisha tribes. They were also joined by the

Hadendoa Beja,

who were rallied to the Mahdi by an Ansār captain in east of Sudan in 1883, Osman Digna.

Although the Mahdist revolution started in June 1881 in Northern Sudan and was backed by western Sudan but it found a great support from the Nuer, Shilluk and Anuak tribes from southern Sudan in addition to the tribes of Bahr Alghazal, a thing which affirmed that the Mahdist revolution was a national revolution and not a regional one.

The Khatmiyya sufi order which had enjoyed popular support in east and north Sudan rejected the Mahdi's claim outright. Mahdist forces attacked the Khatmiyya adherents and even ransacked the tomb of sayyid

Al-Hassan grandson of the revered religious leader Mohammed Uthman al-Mirghani al-Khatim in Kassala. The head of the Khatmiyya sufi order was forced into exile in Egypt for fear of assassination.

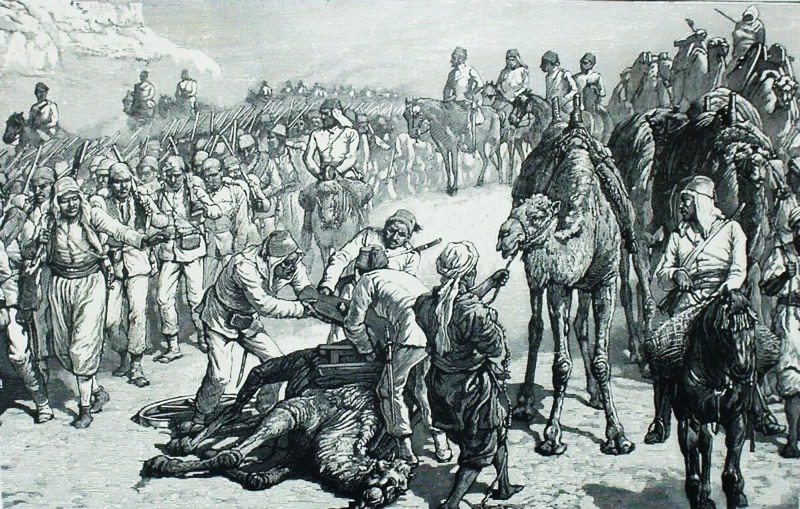

Late in 1883, the Ansār, armed only with spears and swords, overwhelmed a 4,000-man Egyptian

ot far from Al Ubayyid ("El Obeid"),

and seized their rifles and ammunition. The Mahdi followed up this victory by laying siege to al-Ubayyid and starving it into submission after four months. The town remained the headquarters of the Ansar for much of the decade.

The Ansār, now 40,000 strong, then defeated an 8,000-man Egyptian relief force led by British officer William Hicks at Sheikan, in the battle of El Obeid.

The defeat of Hicks sealed the fate of Darfur, which until then had been effectively defended by Rudolf Carl von Slatin.

Jabal Qadir in the south was also taken. The western half of Sudan was now firmly in Ansārī hands.

Their success emboldened the Hadendoa, who under the generalship of Osman Digna wiped out a smaller force of Egyptians under the command of Colonel Valentine Baker

near the Red Sea port of Suakin

. Major-General Gerald Graham

was sent with a force of 4,000 British soldiers and defeated Digna at el teb

on February 29, but were themselves hard-hit two weeks later at Tamai.

Graham eventually withdrew his forces.

Colonel William Hicks (also known as Hicks Pasha, 1830–1883), British soldier, entered the Bombay Army in 1849, and served through the Indian mutiny, being mentioned in despatches for good conduct at the action of Sitka Ghaut in 1859.

In 1861 he became captain, and in the Abyssinian expedition of 1867–1868 was a brigade major, being again mentioned in despatches and given a brevet majority. He retired with the honorary rank of colonel in 1880

Colonel William Hicks (also known as Hicks Pasha, 1830–1883), British soldier, entered the Bombay Army in 1849, and served through the Indian mutiny, being mentioned in despatches for good conduct at the action of Sitka Ghaut in 1859.

In 1861 he became captain, and in the Abyssinian expedition of 1867–1868 was a brigade major, being again mentioned in despatches and given a brevet majority. He retired with the honorary rank of colonel in 1880.

After the close of the 1882 Anglo-Egyptian War, he entered the Khedive's service and was made a pasha. In 1881, Sudan was controlled by Egypt; Muhammad Ahmad proclaimed himself Mahdi and began conquering neighboring territory and thus threatening the precarious Egyptian control of the territory. Early in 1883 he went to Khartoum as chief of the staff of the army there, then commanded by Suliman Niazi Pasha. Camp was formed at Omdurman and a new force of some 8000 fighting men collected—mostly recruited from the

fellahin of Arabi's disbanded troops, sent in chains from Egypt. After a month's vigorous drilling Hicks led 5000 of his men against an equal force of dervishes in Sennar, whom he defeated, and cleared the country between the towns of Sennar

and Khartoum of rebels.

Relieved of the fear of an immediate attack by the mahdists the Egyptian officials at Khartoum intrigued against Hicks, who in July tendered his resignation.

This resulted in the dismissal of Suliman Niazi and the appointment of Hicks as commander-in-chief of an expeditionary force to Kordofan

with orders to crush the mahdi, who in January 1883 had captured El Obeid, the capital of that province. Hicks, aware of the worthlessness of his force for the purpose contemplated, stated his opinion that it would be best to "wait for Kordofan to settle itself" (telegram of 5 August).

The Egyptian ministry, however, did not then believe in the power of the mahdi, and the expedition started from Khartoum on 9 September. It was made up of 7000 infantry, 1000 cavalry and 2000 camp followers and included thirteen Europeans.

On the 10th the force left the Nile at Duem and struck inland across the almost waterless wastes of Kordofan for Obeid. On 5 November the army, misled by treacherous guides and thirst-stricken, was ambushed in dense forest at Kashgil, 30 miles south of Obeid. With the exception of some 300 men the whole force was killed. (See the Battle of El Obeid).

According to the story of Hicks's cook, one of the survivors, the general was the last officer to fall, pierced by the spear of the khalifa Mahommed Sherif. After emptying his revolver the pasha kept his assailants at bay for some time with his sword, a body of Baggara who fled before him being known afterwards as "Baggar Hicks" (the cows driven by Hicks), a play on the words baggara and baggar, the former being the herdsmen and the latter the cows. Hicks's head was cut off and taken to the mah

Given their general lack of interest in the area, the British decided to abandon the Sudan in December 1883, holding only several northern towns and Red Sea ports, such as Khartoum, Kassala, Sannar, and Sawakin. The evacuation of Egyptian troops and officials and other foreigners from Sudan was assigned to General Gordon, who had been reappointed governor general with orders to return to Khartoum and organize a withdrawal of the Egyptian garrisons there.

Gordon reached Khartoum in February 1884. At first he was greeted with jubilation as many of the tribes in the immediate area were at odds with the Mahdists. Transportation northward was still open and the telegraph lines intact. However, the uprising of the Beja soon after his arrival changed things considerably, reducing communications to runners.

Gordon considered the routes northward to be too dangerous to extricate the garrisons and so pressed for reinforcements to be sent from Cairo to help with the withdrawal. He also suggested that his old enemy Al-Zubayr Rahma Mansur, a fine military commander, be given tacit control of the Sudan in order to provide a counter to the Ansār. London rejected both proposals, and so Gordon prepared for a fight.

In March 1884, Gordon tried a small offensive to clear the road northward to Egypt but a number of the officers in the Egyptian force went over to the enemy and their forces fled the field after firing a single salvo. This convinced him that he could carry out only defensive operations and he returned to Khartoum to construct defensive works.

By April 1884, Gordon had managed to evacuate some 2500 of the foreign population that were able to make the trek northwards. His mobile force under Colonel Stewart then returned to the city after repeated incidents where the 200 or so Egyptian forces under his command would turn and run at the slightest provocation.

That month the Ansār reached Khartoum and Gordon was completely cut off. Nevertheless, his defensive works, consisting mainly of mines, proved so frightening to the Ansār that they were unable to penetrate into the city. Stewart maintained a number of small skirmishes using gunboats on the Nile once the waters rose, and in August managed to recapture Berber for a short time. However, Stewart was killed soon after in another foray from Berber to Dongola, a fact Gordon only learned about in a letter from the Mahdi himself.

Under increasing pressure from the public to support him, the British Government under Prime Minister Gladstone eventually ordered Lord Garnet Joseph Wolseley to relieve Gordon. He was already deployed in Egypt due to the attempted coup there earlier, and was able to form up a large force of infantry, moving forward at an extremely slow rate. Realizing they would take some time to arrive, Gordon pressed for him to send forward a "flying column" of camel-borne troops across the Bayyudah Desert from Wadi Halfa under the command of Brigadier-General Sir Herbert Stuart. This force was attacked by the Hadendoa Beja, or "Fuzzy Wuzzies", twice, first at the Battle of Abu Klea and two days later nearer Metemma. Twice the British square held and the Mahdists were repelled with heavy losses.

At Metemma, 100 miles (160 km) north of Khartoum, Wolseley's advance guard met four of Gordon's steamers, sent down to provide speedy transport for the first relieving troops. They gave Wolseley a dispatch from Gordon claiming that the city was about to fall. However, only moments later a runner brought in a message claiming the city could hold out for a year. Deciding to believe the latter, the force stopped while they refit the steamers to hold more troops.

They finally arrived in Khartoum on 28 January 1885 to find the town had fallen during the Battle of Khartoum two days earlier. When the Nile had receded from flood stage, Faraz Pasha had opened the river gates and let the Ansār in. The garrison was slaughtered, and Gordon was killed fighting the Mahdi's warriors on the steps of the palace, hacked to pieces and beheaded which the Mahdi forbade. When Gordon's head was unwrapped at the Mahdi's feet, he ordered the head transfixed between the branches of a tree "....where all who passed it could look in disdain, children could throw stones at it and the hawks of the desert could sweep and circle above." When Wolseley's force arrived, they retreated after attempting to force their way to the center of the town on ships, being met with a hail of fire.The military correspondent of the “Daily News” at Dongola, wrote : “Two men arrived

140here yesterday, April 11th, 1885, whose story throws some light on the capture of Khartoum. They were soldiers in Gordon’s army, taken at the time and sold as slaves, but who ultimately escaped. Their names are Said Abdullah and Jacoob Mahomet. I will let them tell their own history.” “After stating they were first taken at Omdurman, subsequently to the capture of Khartoum; were then stolen by arabs and sold to two Kabbabish merchants, and afterwards escaped from Aboudom to Debbah, from which place they had reached Dongola; they went on to relate the doings of Farig Pasha previously to the taking of Khartoum. I have given you some account of the story by telegraph, and it has been partly made familiar substantially through other channels. They continued: “That night Khartoum was delivered into the hands of the rebels. It fell through the treachery of the accursed Farig Pasha, the Circassian, who opened the gate. May he never reach Paradise! May Shaytan take possession of his soul! But it was Kismet. The gate was called Bouri’; it was on the Blue Nile. We were on guard near, but did not see what was going on. We were

attacked and fought desperately at the gate. Twelve of our staff were killed, and twenty-two of us retreated to a high room, where we were taken prisoners, and now came the ending. The red Flag with the crescent was destined no more to wave over the Palace; nor would the strains of the hymns of His Excellency be heard any more at eventide in Khartoum. Blood was to flow in her streets, in her dwellings, in her very mosque, and on the Kenniseh of the Narsira. A cry arose, “To the Palace! to the Palace!” A wild and furious band rushed towards it, but they were resisted by the black troops, who fought desperately. They knew there was no mercy for them, and that even were their lives spared, they would be enslaved, and the state of the slave, the perpetual bondage with hard taskmasters, is worse than death. Slaves are not treated well, as you think; heavy chains are round their ankles and middle, and they are lashed for the least offence until blood flows. We had fought for the Christian Pasha and for the Turks, and we knew that we should receive no mercy. The house was set on fire: the fight raged and the slaughter continued till the

streets were slippery with blood. The rebels rushed onward to the Palace. We saw a mass rolling to and fro, but did not see Gordon Pasha killed. He met his fate, we believe, as he was leaving the Palace, near the large tree which stands on the esplanade. The Palace is not a stone’s throw, or at any rate a gun shot distance from the Austrian Consul’s house. He was going in that direction, to the magazine on the Kenniseh, a long way off. We did not hear what became of his body, nor did we hear that his head was cut off; but we saw the head of the traitor Farig Pasha, who met with his deserts. We have heard it was the blacks that ran away; and that the Egyptian soldiers fought well; that is not true, they were craven. Had it not been for them, in spite of the treachery of many within the town, the Arabs would not have got in, for we watched the traitors. And now fearful scenes took place in every house and building, in the large Market Place, in the small bazaars; men were slain crying for mercy, but mercy was not in the hearts of those savage enemies. Women and children were robbed of their jewels of silver, of their bracelets, necklaces of precious

stones, and carried off to be sold to the Bishareen merchants as slaves. Yes, and white women too, mother and daughter alike were carried off from their homes of comfort. Wives and children of Egyptian merchants, formerly rich, owning ships and mills; these were sold afterwards, some for 340 thaleries or more, some for 25, according to age and good looks. And the poor black women already slaves, and their children, 70 or 80 thaleries. Their husbands and masters were slain before their eyes . . . . this fighting and spilling of blood continued till noon, till the sun rode high in the sky. There was riot, wrangling, hubbub and cursing, till the hour of evening prayer. But the Muezzin was not called, neither were any prayers offered up at the Moslem Mosque on that dark day in the annals of Khartoum. Meanwhile the screeching devils bespattered with gore, swarming about in droves and bands, found very little plunder, so were disappointed, and sought out Farig Pasha, and found him with the Dervishes. ‘Where is the hidden treasure?’ they at once demanded of him. ‘We know that you are acquainted with the hiding place. Where is the

p. 144money and riches of the city and its merchants? We know that those who left Khartoum did not take away their valuables, and you know where it is hid.’ The Dervishes seeing the tumult questioned him sharply, and addressed him thus: “The long expected one our Lord, desires to know where the English Pasha hid his wealth. We know he was very rich, and every day paid large sums of money; that has not been concealed from our Lord. Now therefore let us know that we may bear him word where all the money is hidden. Let him be bound in the inner chamber and examined; and the gates closed against the Arabs.” Farig was then questioned, but he “swore by Allah and by the souls of his fathers back to three generations, that Gordon had no money, and that he knew of no hidden treasure.” “You lie (cried the Dervishes); you wish after a while to come and dig it out yourself. Listen to what we are going to say to you. We are sure you know where the money is hidden. We are not careful of your life, for you have betrayed the man whose salt you had eaten; you have been the servant of the infidel, and you have betrayed even him.

p. 145Unless you unfold this secret of the buried treasure, you will surely die.” Farig with proud bearing said, “I care not for your threats. I have told you the truth, Allah knows. There is no money, neither is there treasure. You are fools to suppose there is. I have done a great deed, I have delivered to your lord and master (the Madhi), the city which you never could have taken without my help. I tell you again there is no treasure, and you will rue the day if you kill me.”

One of the Dervishes then stepped forward and struck him, bound as he was, in the mouth; then another rushed at him with his two-edged sword, struck him behind the neck so that with this one blow his head fell from his shoulders; (so perished the arch traitor); may his soul be afflicted! But as for Gordon Pasha the magnanimous, may his soul have peace!” The story of these men may, or may not be true, but it seems on the face of it trustworthy.

It is, however, out of harmony with the description given of Gordon’s death by Slatin Pasha, who was taken a prisoner at the time of the fall of Khartoum, and had been kept for

p. 146eleven years in captivity, but eventually made his escape. He was in attendance at the International Geographical Congress held at the Imperial Institute, and devoted to African affairs, when he told the story of his escape from Khartoum. He says “The City of Khartoum fell on the 16th Jan., 1885, and Gordon was killed on the highest step of the staircase of his Palace. His head was cut off and exhibited to Slatin whilst the latter was in chains, with expressions of derision and contempt.”

We have no doubt now as to the fact that Gordon Pasha, the illustrious, the saintly, the brave defender, died doing his duty. In all civilized lands there are still men who tell of Gordon Pasha’s unbounded benevolence; of his mighty faith, of his heroism and self-sacrifice, and they mourn with us the loss of one of the most saintly souls our world has ever known.

The Mahdi Army continued its sweep of victories. Kassala

and Sannar fell soon after and by the end of 1885 the Ansār had begun to move into the southern regions of Sudan. In all Sudan, only Suakin,

reinforced by Indian troops, and Wadi Halfa

on the northern frontier remained in Anglo-Egyptian hands.

With Sudan now in Sudanese hands, the Mahdi formed a government. The

Mahdiyya (Mahdist regime) modified the Shariah, (Islamic law) which would be implemented by Islamic courts headed by various Islamic imams, in accordance with the view of an Islamic state. The courts enforced a Sharia law that the Mahdi claimed was founded on instructions conveyed to him by God in visions.

According to this doctrine loyalty to him was essential to true belief. The recitation of the shahada was modified to include

and Muhammad Ahmad is the Mahdi of God and the representative of His Prophet. Among the five pillars, service in the "jihād" replaced the hajj (pilgrimage to Mecca) as a duty incumbent on the faithful (though Jihad-struggle is central to orthodox Islam, it is not considered one of the five pillars of faith).

He also authorized the burning of lists of pedigrees and books of law and theology because of their association with the old regime and because he believed that they accentuated tribalism at the expense of religious unity.

The rebuilt tomb of Muhammad Ahmad in Omdurman

Six months after the capture of Khartoum, Muhammad Ahmad died of typhus. He was buried in Omdurman near the ruins of Khartoum. The Mahdi had planned for this eventuality and chosen three deputies to replace him, in imitation of the Prophet Muhammad. This led to a long period of disarray, due to rivalry among the three, each supported by people of his native region. This continued until 1891, when Abdallahi ibn Muhammad, with the help primarily of the Baqqara Arabs, emerged as unchallenged leader. Abdallahi, referred to as the "Khalifa" (Caliph, lit. "successor"), purged the

Mahdiyya of members of the Mahdi's family and many of his early religious disciples.

The "Khalifa" was committed to the Mahdi's vision of extending the Mahdiyah through jihād, which led to strained relations with practically every neighboring nation in Africa. For example, the "Khalifa" rejected an offer of an alliance against the Europeans by Ethiopia's Emperor, Yohannes IV

because the majority of the Ethiopians were not Muslim which made them less in the eyes of the Khalifa. Instead, in 1887 a 60,000-man Ansar army invaded Ethiopia, penetrated as far as Gonder,

and captured prisoners and booty. The Khalifa continued to refuse to conclude hostilities or negotiate peace with Ethiopia unless every Ethiopian converted to Islam.

Robert George Talbot Kelly "The Flight of the Khalifa after his Defeat at the Battle of Omdurman, 2nd September 1898"

In March 1889, an Ethiopian force commanded personally by the

Nəgusa nagast (Emperor, lit. "King of Kings") invaded the Sudan and marched on Gallabat; however, after Yohannes IV fell in battle, the Ethiopians withdrew.

After the final defeat of the Khalifa by the British under General Kitchener in 1898, Muhammad Ahmad's tomb was destroyed by the British to prevent it from becoming a rallying point for his supporters, and his bones were thrown into the Nile. Kitchener retained his skull.Allegedly the skull was later buried at Wadi Halfa. The tomb was eventually rebuilt.

Muhammed Ahmad's posthumous son, Abd al-Rahman al-Mahdi, became a leader of the neo-Mahdist movement in the Anglo-Egyptian Sudan whom the British considered important as a moderate leader of the Mahdists. However, the British would not support 'Abd al-Rahman in his ambition to become King of Sudan when the country gained independence.'Abd al-Rahman sponsored the Ummah (Nation) political Party in the period before and just after Sudan became independent in 1956

In modern-day Sudan, Muhammad Ahmad is sometimes seen as a precursor of Sudanese nationalism. The Umma party claim to be his political descendants. Their leader Imam Sadiq al-Mahdi, is the great great grandson of Muhammad Ahmad and also the imam of the Ansar, the religious order that pledges allegiance to Muhammad Ahmad. Sadiq al-Mahdi was Prime Minister of Sudan on two occasions: first briefly in 1966–67, and then between 1986 and 1989.

Naplessharpshooter 1860

Naplessharpshooter 1860 This battle was considered by Garibaldi to be one of his crowning glories - not only did he beat a force twice the size of his own, thus giving his troops the spirit to prevail elsewhere (notably at

This battle was considered by Garibaldi to be one of his crowning glories - not only did he beat a force twice the size of his own, thus giving his troops the spirit to prevail elsewhere (notably at  Palermo), but the ferocity of the troops on both sides proved conclusively for him that Italians could fight.

Palermo), but the ferocity of the troops on both sides proved conclusively for him that Italians could fight.

these britains size Neopolitan infantry and garibaldini would be a good size for a larger size battle. I sell these.

these britains size Neopolitan infantry and garibaldini would be a good size for a larger size battle. I sell these.

Garibaldian 54mm

Garibaldian 54mm

Naplessharpshooter 1860

Naplessharpshooter 1860 This battle was considered by Garibaldi to be one of his crowning glories - not only did he beat a force twice the size of his own, thus giving his troops the spirit to prevail elsewhere (notably at

This battle was considered by Garibaldi to be one of his crowning glories - not only did he beat a force twice the size of his own, thus giving his troops the spirit to prevail elsewhere (notably at  Palermo), but the ferocity of the troops on both sides proved conclusively for him that Italians could fight.

Palermo), but the ferocity of the troops on both sides proved conclusively for him that Italians could fight.

these britains size Neopolitan infantry and garibaldini would be a good size for a larger size battle. I sell these.

these britains size Neopolitan infantry and garibaldini would be a good size for a larger size battle. I sell these.

Garibaldian 54mm

Garibaldian 54mm

.JPG)

.JPG&container=blogger&gadget=a&rewriteMime=image%2F*)

.JPG&container=blogger&gadget=a&rewriteMime=image%2F*)

.JPG&container=blogger&gadget=a&rewriteMime=image%2F*)

France, during the Six Days Campaign of the Napoleonic Wars.

France, during the Six Days Campaign of the Napoleonic Wars. It was fought on 11 February 1814 and resulted in the victory of the French under Emperor Napoleon I over the Russians under

It was fought on 11 February 1814 and resulted in the victory of the French under Emperor Napoleon I over the Russians under  General Fabian Wilhelm von Osten-Sacken and the Prussians under

General Fabian Wilhelm von Osten-Sacken and the Prussians under  General

General

Champaubert, Napoleon

Champaubert, Napoleon

the battle as a volunteer Jäger.

the battle as a volunteer Jäger.

religious sects of the time. More broadly, the Mahdiyya, as Muhammad Ahmad's movement was called, was influenced by earlier Mahdist movements in West Africa, as well as Wahabism

religious sects of the time. More broadly, the Mahdiyya, as Muhammad Ahmad's movement was called, was influenced by earlier Mahdist movements in West Africa, as well as Wahabism  and other puritanical forms of Islamic revivalism that developed in reaction to the growing military and economic dominance of the European powers throughout the 19th century.

and other puritanical forms of Islamic revivalism that developed in reaction to the growing military and economic dominance of the European powers throughout the 19th century.

the Mahdiyya were established and promulgated among the growing ranks of the Mahdi's supporters. After Muhammad Ahmad's unexpected death on 22 June 1885, a mere six months after the conquest of

the Mahdiyya were established and promulgated among the growing ranks of the Mahdi's supporters. After Muhammad Ahmad's unexpected death on 22 June 1885, a mere six months after the conquest of  Khartoum, his chief deputy, Abdallahi ibn Muhammad took over the administration of the nascent Mahdist state.

Khartoum, his chief deputy, Abdallahi ibn Muhammad took over the administration of the nascent Mahdist state. in Northern Sudan to a family of descendants of the Prophet Muhammad through the line of his grandson Hassan. As a child, the family moved to the town of Karari, north of Omdurman,

in Northern Sudan to a family of descendants of the Prophet Muhammad through the line of his grandson Hassan. As a child, the family moved to the town of Karari, north of Omdurman, where Muhammad Ahmad's father, Abdullah, could find a supply of timber for his boat-building business.

where Muhammad Ahmad's father, Abdullah, could find a supply of timber for his boat-building business. e studied first under Sheikh al-Amin al-Suwaylih in the Gezira region around Khartoum, and subsequently under Sheikh Muhammad al-Dikayr 'Abdallah Khujali near the town of Berber in North Sudan. Determined to live a life of asceticism, mysticism and worship, i

e studied first under Sheikh al-Amin al-Suwaylih in the Gezira region around Khartoum, and subsequently under Sheikh Muhammad al-Dikayr 'Abdallah Khujali near the town of Berber in North Sudan. Determined to live a life of asceticism, mysticism and worship, i he sought out Sheikh Muhammad Sharif Nur al-Dai'm, the grandson of the founder of the Samaniyya Sufi sect in Sudan.

he sought out Sheikh Muhammad Sharif Nur al-Dai'm, the grandson of the founder of the Samaniyya Sufi sect in Sudan.  Muhammad Ahmad stayed with Sheikh Muhammad Sharif for seven years, during which time he was recognized for his piety and as

Muhammad Ahmad stayed with Sheikh Muhammad Sharif for seven years, during which time he was recognized for his piety and as nd of this period, he was awarded the title of Sheikh himself, and began to travel around the country on religious missions. He was permitted to give tariqa and Uhūd to new followers.

nd of this period, he was awarded the title of Sheikh himself, and began to travel around the country on religious missions. He was permitted to give tariqa and Uhūd to new followers.

gained a notable reputation among the local population as an excellent speaker and mystic.

gained a notable reputation among the local population as an excellent speaker and mystic. The broad thrust of his teaching followed that of other reformers, his Islam was one devoted to the words of Muhammad and based on a return to the virtues of strict devotion, prayer

The broad thrust of his teaching followed that of other reformers, his Islam was one devoted to the words of Muhammad and based on a return to the virtues of strict devotion, prayer mplicity as laid down in the Qur'an. Any deviation from the Qur'an was therefore heresy.

mplicity as laid down in the Qur'an. Any deviation from the Qur'an was therefore heresy.

Despite initially amicable relations, in 1878 the two religious leaders had a dispute motivated by Sheikh Sharif's resentment of his former student's growing popularity. The dispute led to violence between their followers, and while they temporarily reconciled their differences, the experience revealed to Muhammad Ahmad his mentor's ostensible faults. At a subsequent celebration in honor of the circumcision of Sheikh Sharif's sons, Muhammad Ahmad expressed his disapproval of the dancing and music, which reignited the latent tension between the two men. As a result of this second dispute, Sheikh Sharif expelled his former student from the Samaniyya order, and despite numerous apologies and emotional appeals, refused to forgive and re-admit him.

Despite initially amicable relations, in 1878 the two religious leaders had a dispute motivated by Sheikh Sharif's resentment of his former student's growing popularity. The dispute led to violence between their followers, and while they temporarily reconciled their differences, the experience revealed to Muhammad Ahmad his mentor's ostensible faults. At a subsequent celebration in honor of the circumcision of Sheikh Sharif's sons, Muhammad Ahmad expressed his disapproval of the dancing and music, which reignited the latent tension between the two men. As a result of this second dispute, Sheikh Sharif expelled his former student from the Samaniyya order, and despite numerous apologies and emotional appeals, refused to forgive and re-admit him.

who were enmeshed in a power struggle between two rival claimants to the governorship of the province. While in Kordofan, he also enhanced his reputation by granting baraka to the common people who attended his sermons en masse

who were enmeshed in a power struggle between two rival claimants to the governorship of the province. While in Kordofan, he also enhanced his reputation by granting baraka to the common people who attended his sermons en masse

In part, his claim was based on his status as a prominent Sufi sheikh with a large following in the Samaniyya order and among the tribes in the area around Aba Island Yet the idea of the Mahdiyya had been central to the belief of the Samaniyya prior to Muhammad Ahmad's manifestation. The previous Samaniyya leader, Sheikh al-Qurashi Wad al-Z

In part, his claim was based on his status as a prominent Sufi sheikh with a large following in the Samaniyya order and among the tribes in the area around Aba Island Yet the idea of the Mahdiyya had been central to the belief of the Samaniyya prior to Muhammad Ahmad's manifestation. The previous Samaniyya leader, Sheikh al-Qurashi Wad al-Z ad asserted that the long-awaited-for redeemer would come from the Samaniyya line. According to Sheikh al-Qurashi, the Mahdi would make himself known through a number of signs, some established in the early period of Islam and recorded in the Hadith literature, and others having a more distinctly local origin, such as the prediction that the Mahdi would ride the sheikh's pony and erect a dome over his grave after his death.

ad asserted that the long-awaited-for redeemer would come from the Samaniyya line. According to Sheikh al-Qurashi, the Mahdi would make himself known through a number of signs, some established in the early period of Islam and recorded in the Hadith literature, and others having a more distinctly local origin, such as the prediction that the Mahdi would ride the sheikh's pony and erect a dome over his grave after his death. opponents, Muhammad Ahmad claimed that he had been appointed as the Mahdi by a prophetic assembly or hadra (Arabic: Al-Hadra Al-Nabawiyya, الحضرة النبوية). A hadra, in the Sufi tradition, is a gathering of all

opponents, Muhammad Ahmad claimed that he had been appointed as the Mahdi by a prophetic assembly or hadra (Arabic: Al-Hadra Al-Nabawiyya, الحضرة النبوية). A hadra, in the Sufi tradition, is a gathering of all  the prophets from the time of Adam to Muhammad, as well as many Sufi holy men who are believed to have reached the highest level of affinity with the divine during their lifetime. The hadra is chaired by the Prophet

the prophets from the time of Adam to Muhammad, as well as many Sufi holy men who are believed to have reached the highest level of affinity with the divine during their lifetime. The hadra is chaired by the Prophet Muhammad, known as Sayyid al-Wujud, and at his side are the seven Qutb, the most senior of whom is known as Ghawth az-Zaman. In the belief system of the Mahdiyya, it was this divine assembly that bestowed upon Muhammad Ahmad the title of al-Mahdi.

Muhammad, known as Sayyid al-Wujud, and at his side are the seven Qutb, the most senior of whom is known as Ghawth az-Zaman. In the belief system of the Mahdiyya, it was this divine assembly that bestowed upon Muhammad Ahmad the title of al-Mahdi.

that he lacked proof of descent from Fatima, that he did not have the prophesied physical characteristics of the Mahdi, and that his manifestation did not conform with the "time of troubles" "when the land is filed with oppression, tryanny, and enmity."

that he lacked proof of descent from Fatima, that he did not have the prophesied physical characteristics of the Mahdi, and that his manifestation did not conform with the "time of troubles" "when the land is filed with oppression, tryanny, and enmity."

![[Illustration]](http://www.heritage-history.com/books/langjean/gordon/zpage104.gif)

(known in the West as "the Dervishes"), made a long march to Kurdufan. There he gained a large number of recruits, especially from the Baqqara, and notable leaders such as Sheikh Madibbo ibn Ali of Rizeigat and Abdallahi ibn Muhammad of Ta'aisha tribes. They were also joined by the

(known in the West as "the Dervishes"), made a long march to Kurdufan. There he gained a large number of recruits, especially from the Baqqara, and notable leaders such as Sheikh Madibbo ibn Ali of Rizeigat and Abdallahi ibn Muhammad of Ta'aisha tribes. They were also joined by the  Hadendoa Beja,

Hadendoa Beja, who were rallied to the Mahdi by an Ansār captain in east of Sudan in 1883, Osman Digna.

who were rallied to the Mahdi by an Ansār captain in east of Sudan in 1883, Osman Digna.

ot far from Al Ubayyid ("El Obeid"),

ot far from Al Ubayyid ("El Obeid"),  and seized their rifles and ammunition. The Mahdi followed up this victory by laying siege to al-Ubayyid and starving it into submission after four months. The town remained the headquarters of the Ansar for much of the decade.

and seized their rifles and ammunition. The Mahdi followed up this victory by laying siege to al-Ubayyid and starving it into submission after four months. The town remained the headquarters of the Ansar for much of the decade.

The defeat of Hicks sealed the fate of Darfur, which until then had been effectively defended by Rudolf Carl von Slatin.

The defeat of Hicks sealed the fate of Darfur, which until then had been effectively defended by Rudolf Carl von Slatin. Jabal Qadir in the south was also taken. The western half of Sudan was now firmly in Ansārī hands.

Jabal Qadir in the south was also taken. The western half of Sudan was now firmly in Ansārī hands.

near the Red Sea port of Suakin

near the Red Sea port of Suakin . Major-General Gerald Graham

. Major-General Gerald Graham was sent with a force of 4,000 British soldiers and defeated Digna at el teb

was sent with a force of 4,000 British soldiers and defeated Digna at el teb on February 29, but were themselves hard-hit two weeks later at Tamai.

on February 29, but were themselves hard-hit two weeks later at Tamai. Graham eventually withdrew his forces.

Graham eventually withdrew his forces.

and Khartoum of rebels.

and Khartoum of rebels. with orders to crush the mahdi, who in January 1883 had captured El Obeid, the capital of that province. Hicks, aware of the worthlessness of his force for the purpose contemplated, stated his opinion that it would be best to "wait for Kordofan to settle itself" (telegram of 5 August).

with orders to crush the mahdi, who in January 1883 had captured El Obeid, the capital of that province. Hicks, aware of the worthlessness of his force for the purpose contemplated, stated his opinion that it would be best to "wait for Kordofan to settle itself" (telegram of 5 August).

and Sannar fell soon after and by the end of 1885 the Ansār had begun to move into the southern regions of Sudan. In all Sudan, only Suakin,

and Sannar fell soon after and by the end of 1885 the Ansār had begun to move into the southern regions of Sudan. In all Sudan, only Suakin, on the northern frontier remained in Anglo-Egyptian hands.

on the northern frontier remained in Anglo-Egyptian hands.

because the majority of the Ethiopians were not Muslim which made them less in the eyes of the Khalifa. Instead, in 1887 a 60,000-man Ansar army invaded Ethiopia, penetrated as far as Gonder,

because the majority of the Ethiopians were not Muslim which made them less in the eyes of the Khalifa. Instead, in 1887 a 60,000-man Ansar army invaded Ethiopia, penetrated as far as Gonder, and captured prisoners and booty. The Khalifa continued to refuse to conclude hostilities or negotiate peace with Ethiopia unless every Ethiopian converted to Islam.

and captured prisoners and booty. The Khalifa continued to refuse to conclude hostilities or negotiate peace with Ethiopia unless every Ethiopian converted to Islam.