The 300 Spartans is a 1962 Cinemascope film depicting the Battle of Thermopylae . Made with the cooperation of the Greek government, it was shot in the village of Perachora in the Peloponnese. It starred Richard Egan

. Made with the cooperation of the Greek government, it was shot in the village of Perachora in the Peloponnese. It starred Richard Egan  the Spartan king Leonidas, Ralph Richardson as Themistocles of Athens and David Farrar

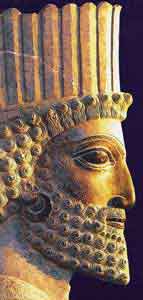

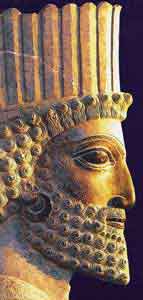

the Spartan king Leonidas, Ralph Richardson as Themistocles of Athens and David Farrar  Persian king Xerxes, with Diane Baker

Persian king Xerxes, with Diane Baker  Ellas and Barry Coe as Phylon providing the requisite romantic element in the film. In the film, a force of Greek warriors led by 300 Spartans fights against a Persian army of almost limitless size. Despite the odds, the Spartans will not flee or surrender, even if it means their deaths.

Ellas and Barry Coe as Phylon providing the requisite romantic element in the film. In the film, a force of Greek warriors led by 300 Spartans fights against a Persian army of almost limitless size. Despite the odds, the Spartans will not flee or surrender, even if it means their deaths.

When it was released in 1962, critics saw the movie as a commentary or referring to the independent Greek states as "the only stronghold of freedom remaining in the then known world", holding out against the Persian "slave empire".

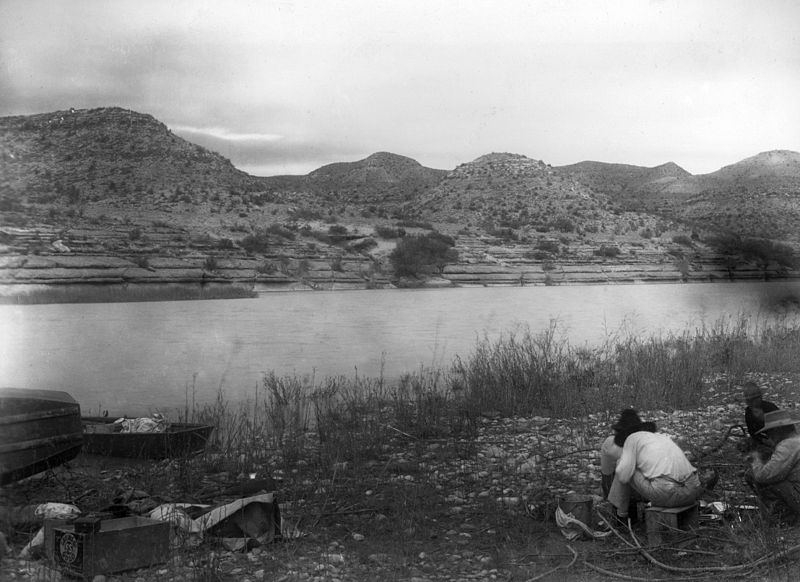

The film was shot near the village of Perachora  on the northern, mainland side of the Corinth canal. It was impossible to shoot at the actual location in Thermopylae because the sea had receded about 3 miles farther away from the narrow pass at the time of the actual battle in 480 B.C. Some 5,000 members of the Royal Hellenic Army were loaned by the King of Greece to portray both the Spartans and the Persians.

on the northern, mainland side of the Corinth canal. It was impossible to shoot at the actual location in Thermopylae because the sea had receded about 3 miles farther away from the narrow pass at the time of the actual battle in 480 B.C. Some 5,000 members of the Royal Hellenic Army were loaned by the King of Greece to portray both the Spartans and the Persians.Xerxes I of Persia

leads a vast army of soldiers into Europe

to defeat the small city-states of Greece

, not only to fulfill the idea of "one world ruled by one master

", but also to avenge the defeat of his father at the Battle of Marathon

ten years before. Accompanying him are Artemisia I

, the Queen of

the Queen of Halicarnassus

,  beguiles Xerxes with her feminine charm, and Demaratus, an exiled king of Sparta, to whose warnings Xerxes pays little heed.

beguiles Xerxes with her feminine charm, and Demaratus, an exiled king of Sparta, to whose warnings Xerxes pays little heed.

In Corinth, Themistocles of Athens wins the support of the Greek allies and convinces both the delegates and the Spartan representative, Leonidas I, to grant Sparta leadership of their forces. Outside the hall, Leonidas and Themistocles agree to fortify the pass at Thermopylae until the rest of the army arrives. After this, Leonidas learns of the Persian advance and travels to Sparta to spread the news.

In Sparta, his fellow king Leotychidas is fighting a losing battle with the Ephors over a religious festival that is due to take place, with members of the council arguing that the army should wait until after the festival is over before it marches, while Leotychidas fears that by that time the Persians may have conquered Greece. Leonidas decides to march north immediately with his personal bodyguard of 300 men, who are exempt from the decisions of the Ephors and the Gerousia. They are subsequently reinforced by Thespians led byDemophilus and other Greek allies.

After several days of fighting, Xerxes grows angry as his army is repeatedly routed by the Greeks, with the Spartans in the forefront. Leonidas receives word that, by decision of the Ephors, the remainder of the Spartan army, rather than joining him as he had expected, will only fortify the isthmus in the Peloponnese and will advance no further. The Greeks constantly beat back the Persians, and following the defeat of his personal bodyguard in battle against the Spartans, Xerxes begins to consider withdrawing to Sardis until he can equip a larger force at a later date. As he prepares to withdraw, however, Xerxes receives word from the treacherous and avaricious Ephialtes of a goat-track through the mountains that will enable his forces to attack the Greeks from the rear. Promising to reward Ephialtes for his betrayal, Xerxes sends his army onward.

Once Leonidas realizes he will be surrounded, he sends away the Greek allies to alert the cities to the south. Being too few to hold the pass, the Spartans instead attack the Persian front, where Xerxes is nearby. Leonidas is killed in the melée. Meanwhile the Thespians, who had refused to leave, are overwhelmed (offscreen) while defending the rear. Surrounded, the surviving Spartans refuse Xerxes's demand to give up Leonidas' body. They are then annihilated by arrowfire.

After this, narration states that the Battle of Salamis and the Battle of Plataea end the Persian invasion, which could not have been organized without the time bought by the 300 Spartans who defied the tyranny of Xerxes at Thermopylae. One of the final images of the film is the memorial bearing the epigram of Simonides of Ceos, which is recited.

"O Stranger, send the news home to the people of Sparta that here we

-

- Are laid to rest: the commands they gave us have been obeyed."

- Richard Egan as King Leonidas, Agiad King of Sparta

- Ralph Richardson as Themistocles of Athens

- Diane Baker as Ellas, daughter of Pentheus and niece of Queen Gorgo

- Barry Coe

as Phyllon, son of Grellas, a Spartan in love with Ellas

as Phyllon, son of Grellas, a Spartan in love with Ellas

- Anna Synodinou as Queen Gorgo, Leonidas' wife

- David Farrar as King Xerxes of the Persian Empire

- Anne Wakefield as Artemisia, Queen of Halicarnassus

- Ivan Triesault as Demaratus, exiled Euripontid ex-King of Sparta

- Nikos Papakonstantinou (1920-1993) as Mardonius, Persian general

- Donald Houston as

Hydarnes, Persian general leader of the Immortals

Hydarnes, Persian general leader of the Immortals

- Robert Brown as Pentheus,

Spartan soldier second-in-command to Leonidas

Spartan soldier second-in-command to Leonidas

- John Crawford as Agathon, Spartan spy and soldier

- Charles Fawcett as Megistias, Spartan priest

- Kieron Moore

as Ephialtes of Trachis

as Ephialtes of Trachis

- Yorgos Moutsios as Grellas, a Spartan in Xerxes' camp

- Dimos Starenios as Samos, a goatherd living in the vicinity of Thermopylae

- Anna Raftopoulou as Toris, Samos' wife

- John Contes as Artovadus, Persian general

- Michalis Nikolinakos as Myron, a Spartan

- Sandro Giglio as Xenathon, a Spartan Ephor

- Laurence Naismith as unnamed Greek delegate

- Marietta Flemotomos as unnamed Greek woman at shield ceremony

7NOn0Q~~60_12.JPG)

after seizing the kingship, Darius I of Persia

(son of Hystaspes) married Atossa

(daughter of Cyrus the Great). They were both descendants of Achaemenes

from different Achaemenid lines. Marrying a daughter of Cyrus strengthened Darius's position as king. Darius was an active emperor, busy with building programs in Persepolis

,

Susa

, Egypt

, and elsewhere. Toward the end of his reign he moved to punish Athens, but a new revolt in Egypt (probably led by the Persian satrap) had to be suppressed. Under Persian law, the Achaemenian kings were required to choose a successor before setting out on such serious expeditions. Upon his great decision to leave (487-486 BC), Darius prepared his tomb at Naqsh-e Rostam

and appointed Xerxes, his eldest son by Atossa, as his successor. Darius's failing health then prevented him from leading the campaigns, and he died in October 486 BC.

and appointed Xerxes, his eldest son by Atossa, as his successor. Darius's failing health then prevented him from leading the campaigns, and he died in October 486 BC.

Artabazanes

claimed the crown as the eldest of all the children, because it was an established custom all over the world for the eldest to have the pre-eminence; while Xerxes, on the other hand, urged that he was sprung from Atossa, the daughter of Cyrus, and that it was Cyrus who had won the Persians their freedom. Some modern scholars also view the unusual decision of Darius to give the throne to Xerxes to be a result of his consideration of the unique positions that Cyrus the Great and his daughter Atossa have had. Artobazan was born to "Darius the subject", while Xerxes was the eldest son born in the purple after Darius's rise to the throne, and Artobazan's mother was a commoner while Xerxes's mother was the daughter of the founder of the empire.

Xerxes was crowned and succeeded his father in October–December 486 BC

[7] when he was about 36 years old.The transition of power to Xerxes was smooth due again in part to the great authority of Atossa and his accession of royal power was not challenged by any person at court or in the Achaemenian family, or any subject nation.

Almost immediately, he suppressed the revolts in Egypt and Babylon that had broken out the year before, and appointed his brother Achaemenes as governor or satrap (Old Persian: khshathrapavan) over Egypt. In 484 BC, he outraged the Babylonians by violently confiscating and melting down the golden statue of Bel (Marduk, Merodach), the hands of which the rightful king of Babylon had to clasp each New Year's Day. This sacrilege led the Babylonians to rebel in 484 BC and 482 BC, so that in contemporary Babylonian documents, Xerxes refused his father's title of King of Babylon, being named rather as King of Persia and Media, Great King, King of Kings (Shahanshah) and King of Nations (i.e. of the world).

Even though Herodotus's report in the Histories has created certain problems concerning Xerxes's religious beliefs, modern scholars consider him a Zoroastrian

was fought between an alliance of Greek city-states

, led by King Leonidas

of Sparta, and the Persian Empire

of Xerxes I

over the course of three days, during the second Persian invasion of Greece

. It took place simultaneously with the naval battle at Artemisium

, in August or September 480 BC, at the narrow coastal pass ofThermopylae

('The Hot Gates'). The Persian invasion was a delayed response to the defeat of the first Persian invasion of Greece

, which had been ended by the Athenian

victory at the Battle of Marathon

in 490 BC. Xerxes had amassed a huge army and navy, and set out to conquer all of Greece. The Athenian general Themistocles

had proposed that the allied Greeks block the advance of the Persian army at the pass of Thermopylae, and simultaneously block the Persian navy at the Straits of Artemisium

.

A Greek force of approximately 7,000 men marched north to block the pass in the summer of 480 BC. The Persian army, alleged by the ancient sources to have numbered over one million but today considered to have been much smaller (various figures are given by scholars ranging between about 100,000 and 300,000),

[7arrived at the pass in late August or early September. The vastly outnumbered Greeks held off the Persians for seven days (including three of battle) before the rear-guard was annihilated in one of history's most famous last stands. During two full days of battle the small force led by King

Leonidas I of

Sparta blocked the only road by which the massive Persian army could pass. After the second day of battle a local resident named Ephialtes betrayed the Greeks by revealing a small path that led behind the Greek lines. Leonidas, aware that his force was being outflanked, dismissed the bulk of the Greek army and remained to guard the rear with 300 Spartans, 700 Thespians, 400 Thebans and perhaps a few hundred others, most of whom were killed.

After this engagement the Greek navy, under the command of the Athenian politician Themistocles, at Artemisium received news of the defeat at Thermopylae. Since the Greek's strategy required both Thermopylae and Artemisium to be held, and given their losses, the withdrawal to Salamis was decided. The Persians overran Boeotia and then captured the evacuated Athens. The Greek fleet, seeking a decisive victory over the Persian armada, attacked and defeated the invaders at the Battle of Salamis in late 480 BC. Fearful of being trapped in Europe, Xerxes withdrew with much of his army to Asia (losing most to starvation and disease), leaving

Mardonius to attempt to complete the conquest of Greece. The following year, however, saw a Greek army decisively defeat the Persians at the Battle of Plataea, thereby ending the Persian invasion.

Both ancient and modern writers have used the Battle of Thermopylae as an example of the power of a patriotic army defending native soil. The performance of the defenders at the battle of Thermopylae is also used as an example of the advantages of training, equipment, and good use of terrain as force multipliers and has become a symbol of courage against overwhelming odds

. Made with the cooperation of the Greek government, it was shot in the village of Perachora in the Peloponnese. It starred Richard Egan

. Made with the cooperation of the Greek government, it was shot in the village of Perachora in the Peloponnese. It starred Richard Egan  the Spartan king Leonidas, Ralph Richardson as Themistocles of Athens and David Farrar

the Spartan king Leonidas, Ralph Richardson as Themistocles of Athens and David Farrar  Persian king Xerxes, with Diane Baker

Persian king Xerxes, with Diane Baker

the Queen of Halicarnassus,

the Queen of Halicarnassus,  beguiles Xerxes with her feminine charm, and Demaratus, an exiled king of Sparta, to whose warnings Xerxes pays little heed.

beguiles Xerxes with her feminine charm, and Demaratus, an exiled king of Sparta, to whose warnings Xerxes pays little heed.

as Phyllon, son of Grellas, a Spartan in love with Ellas

as Phyllon, son of Grellas, a Spartan in love with Ellas Hydarnes, Persian general leader of the Immortals

Hydarnes, Persian general leader of the Immortals Spartan soldier second-in-command to Leonidas

Spartan soldier second-in-command to Leonidas as Ephialtes of Trachis

as Ephialtes of Trachis7NOn0Q~~60_12.JPG)

Susa, Egypt, and elsewhere. Toward the end of his reign he moved to punish Athens, but a new revolt in Egypt (probably led by the Persian satrap) had to be suppressed. Under Persian law, the Achaemenian kings were required to choose a successor before setting out on such serious expeditions. Upon his great decision to leave (487-486 BC), Darius prepared his tomb at Naqsh-e Rostam

Susa, Egypt, and elsewhere. Toward the end of his reign he moved to punish Athens, but a new revolt in Egypt (probably led by the Persian satrap) had to be suppressed. Under Persian law, the Achaemenian kings were required to choose a successor before setting out on such serious expeditions. Upon his great decision to leave (487-486 BC), Darius prepared his tomb at Naqsh-e Rostam and appointed Xerxes, his eldest son by Atossa, as his successor. Darius's failing health then prevented him from leading the campaigns, and he died in October 486 BC.

and appointed Xerxes, his eldest son by Atossa, as his successor. Darius's failing health then prevented him from leading the campaigns, and he died in October 486 BC. claimed the crown as the eldest of all the children, because it was an established custom all over the world for the eldest to have the pre-eminence; while Xerxes, on the other hand, urged that he was sprung from Atossa, the daughter of Cyrus, and that it was Cyrus who had won the Persians their freedom. Some modern scholars also view the unusual decision of Darius to give the throne to Xerxes to be a result of his consideration of the unique positions that Cyrus the Great and his daughter Atossa have had. Artobazan was born to "Darius the subject", while Xerxes was the eldest son born in the purple after Darius's rise to the throne, and Artobazan's mother was a commoner while Xerxes's mother was the daughter of the founder of the empire.

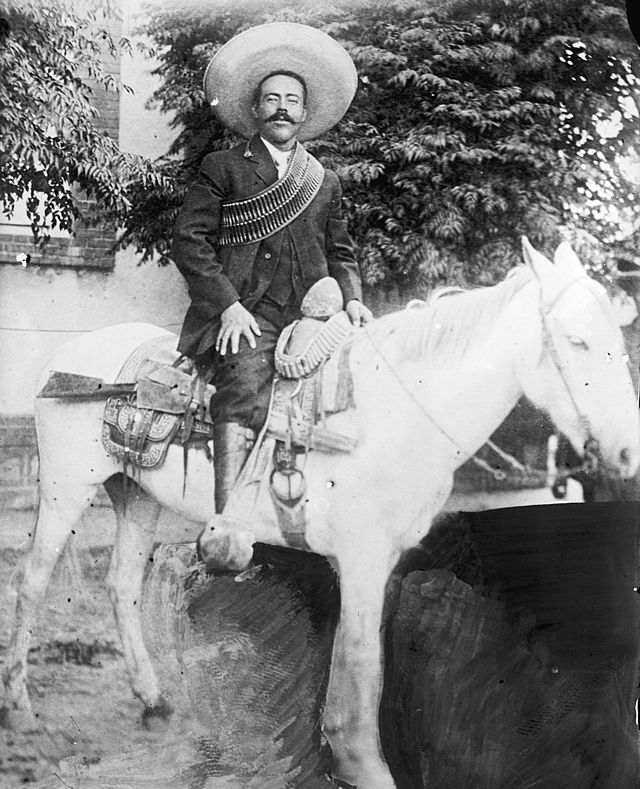

claimed the crown as the eldest of all the children, because it was an established custom all over the world for the eldest to have the pre-eminence; while Xerxes, on the other hand, urged that he was sprung from Atossa, the daughter of Cyrus, and that it was Cyrus who had won the Persians their freedom. Some modern scholars also view the unusual decision of Darius to give the throne to Xerxes to be a result of his consideration of the unique positions that Cyrus the Great and his daughter Atossa have had. Artobazan was born to "Darius the subject", while Xerxes was the eldest son born in the purple after Darius's rise to the throne, and Artobazan's mother was a commoner while Xerxes's mother was the daughter of the founder of the empire. The Border War,or the Mexico has experienced many changes in territorial organization during its history as an independent state.

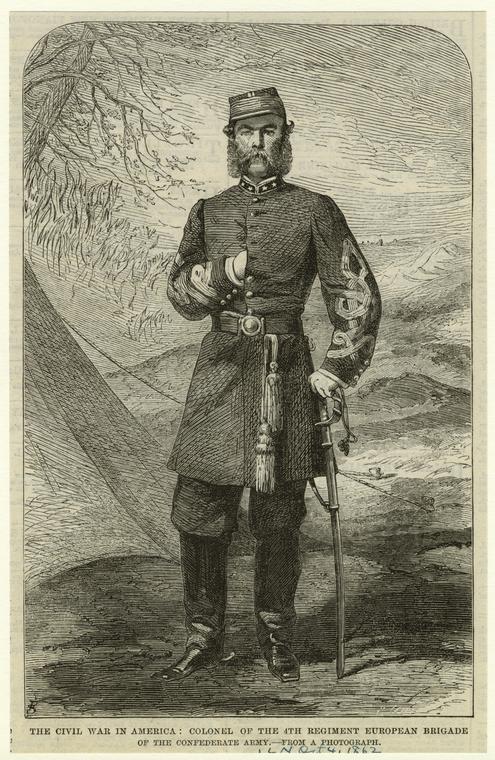

The Border War,or the Mexico has experienced many changes in territorial organization during its history as an independent state.  The territorial boundaries of Mexico were affected by presidential and imperial decrees. One such decree was the Law of Bases for the Convocation of the Constituent Congress to the Constitutive Act of the Mexican Federation, which

The territorial boundaries of Mexico were affected by presidential and imperial decrees. One such decree was the Law of Bases for the Convocation of the Constituent Congress to the Constitutive Act of the Mexican Federation, which the Captaincy General of Guatemala and the autonomous Kingdoms of East and West. The decree resulted in the independence from Spain.The historical roots of today's Texas Ranger Division trace back to the first days of Anglo-American settlement of what is today the State of Texas, when it was part of the Province of Coahuila y Tejas belonging to the newly independent country of Mexico. The unique characteristics that the Rangers adopted during the force's formative years and that give the division its heritage today—characteristics for which the Texas Rangers would become world renowned—have been accounted for by the nature of the Rangers' duties. Which was to protect a thinly populated frontier against protracted hostilities, first with Plains Indian tribes, and after the Texas Revolution, hostilities with Mexico.

the Captaincy General of Guatemala and the autonomous Kingdoms of East and West. The decree resulted in the independence from Spain.The historical roots of today's Texas Ranger Division trace back to the first days of Anglo-American settlement of what is today the State of Texas, when it was part of the Province of Coahuila y Tejas belonging to the newly independent country of Mexico. The unique characteristics that the Rangers adopted during the force's formative years and that give the division its heritage today—characteristics for which the Texas Rangers would become world renowned—have been accounted for by the nature of the Rangers' duties. Which was to protect a thinly populated frontier against protracted hostilities, first with Plains Indian tribes, and after the Texas Revolution, hostilities with Mexico.

took office in January 1874, it marked the end of Reconstruction for the Lone Star State, and he vigorously restored order to Texas in pursuit of improvements to both the economy and security. Once again Indians and Mexican bandits were threatening the frontiers, and once again the Rangers were tasked with solving the problem. That same year, the state legislature authorized the

took office in January 1874, it marked the end of Reconstruction for the Lone Star State, and he vigorously restored order to Texas in pursuit of improvements to both the economy and security. Once again Indians and Mexican bandits were threatening the frontiers, and once again the Rangers were tasked with solving the problem. That same year, the state legislature authorized the

(who later became famous for leading the party that killed the outlaws Bonnie and Clyde),

(who later became famous for leading the party that killed the outlaws Bonnie and Clyde), the Rangers displayed remarkable activity in the following years, including the continuous fighting of cattle rustlers, intervening in the violent labor disputes of the time and protecting the citizenry involved in Ku Klux Klan's public displays from violent mob reaction. With the passage of the Volstead Act and the beginning of the Prohibition on January 16, 1920, their duties extended to scouting the border for tequila smugglers and detecting and dismantling the illegal stills that abounded along Texas's territory.

the Rangers displayed remarkable activity in the following years, including the continuous fighting of cattle rustlers, intervening in the violent labor disputes of the time and protecting the citizenry involved in Ku Klux Klan's public displays from violent mob reaction. With the passage of the Volstead Act and the beginning of the Prohibition on January 16, 1920, their duties extended to scouting the border for tequila smugglers and detecting and dismantling the illegal stills that abounded along Texas's territory.

Conflict was not only subject to Villistas and Americans; Maderistas,Carrancistas, Constitutionalistas and Germans also engaged in battle with American forces during this period. The war was one of the highlights of the Old West era.

Conflict was not only subject to Villistas and Americans; Maderistas,Carrancistas, Constitutionalistas and Germans also engaged in battle with American forces during this period. The war was one of the highlights of the Old West era.